The multi-professional framework for advanced practice by Health Education England (2017) states that advanced care practitioners (ACPs) must use their knowledge, expertise and decision-making skills to inform clinical reasoning and to enable them to make evidence-based clinical decisions and/or diagnoses. ACPs work autonomously, utilising clinical reasoning to ensure safe practice. Clinical reasoning is described as a process whereby a clinician analyses their findings and uses these to formulate a list of causes for the patients' problems (Bickley et al, 2021).

The clinical reasoning cycle

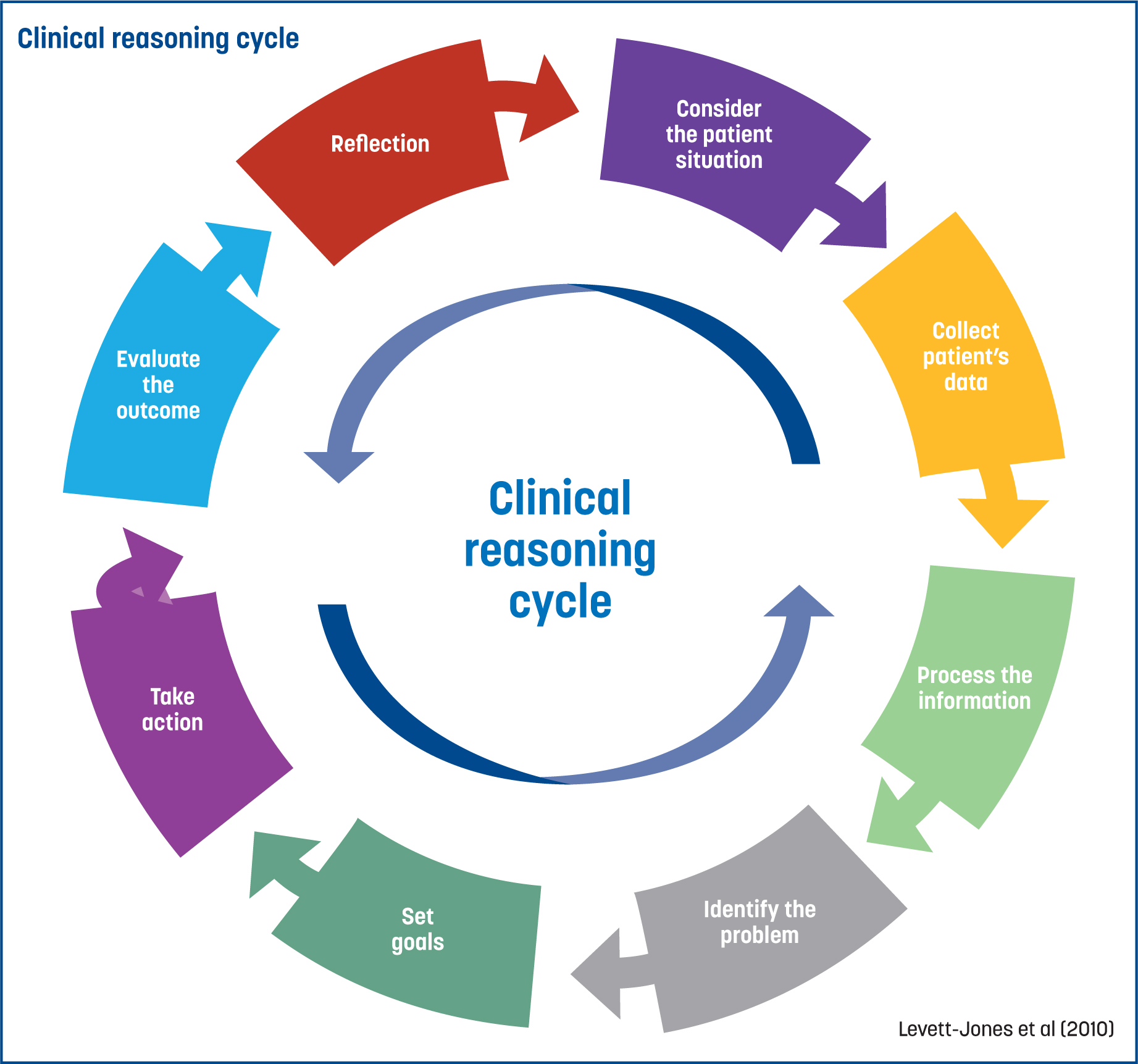

One method of clinical reasoning used in healthcare is the clinical reasoning cycle (CRC) (Levett-Jones et al, 2010). This is an 8-step process whereby clinicians collect cues and patient data, process this information, identify the problem, set goals, take action, evaluate the outcome and reflect on the process (Figure 1). The CRC helps to guide clinicians to make a decision that is in the patient's best interests and is specific to the presenting complaint (James, 2021). Although there are eight sections to the CRC, these are not fixed, which allows the clinician to flow backwards and forwards between the different sections as new information arises or the clinical situation changes (Levett-Jones et al, 2010). In this paper, the CRC was utilised to evaluate the decisions made within the case of a patient who presented to a trainee ACP (tACP) with a respiratory complaint.

Case report

A 47-year-old male, who will be referred to throughout as Pete to protect patient confidentiality, presented to the tACP with a cough. Pete had presented to his GP in primary care 2 weeks beforehand and was treated with doxycycline for a lower respiratory tract infection. Reported symptoms included a non-productive cough with no dyspnoea, orthopnoea or nocturnal dyspnoea, weight loss or haemoptysis, and a normal appetite. On objective examination (Table 1), Pete exhibited a normal facial colour, appearing well perfused with no cyanosis; there was no shortness of breath at rest or exertion as he mobilised into the consultation room. There was no lower limb oedema, and chest examination was normal.

| Observation | Rate |

|---|---|

| Respiratory rate | 16 |

| Heart rate | 73 |

| Peripheral oxygen saturations | 97% |

| Tympanic temperature | 36.4 |

| Blood pressure | 151/89 mmHg |

| Capillary refill time | 2 seconds |

| Glasgow Coma scale | 15 |

| NEWS2 score | 0 |

Several red flags were identified during the consultation, including a 30-year smoking history, a prolonged cough and occupational risk (prior work within a sawmill) (Turner, 2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2024). However, red flags alone are not reliable indicators of serious pathology (Turner, 2019), and consideration of all assessment findings, subjective and objective, are essential within the clinical reasoning process.

Cough

The first stage of the CRC explored the patient situation (Levett-Jones et al, 2010). Cough is a common presentation in primary care in the UK, with 48 million presentations per year, with the majority of these being viral infections, rather than bacterial, requiring antibiotic therapy (NICE, 2019; Searle-Barnes and Phillips, 2020). In this case, Pete presented with an ongoing cough, classified as acute/subacute. A cough can be challenging for clinicians to diagnose and manage (Rouadi et al, 2022). It can be classified as acute, lasting less than 3 weeks; sub-acute, lasting between 3–8 weeks; or chronic, lasting more than 8 weeks (NICE, 2023).

Information gathered from the subjective assessment (CRC part 2) informed potential differential diagnoses (Box 1). A respiratory examination (Table 1) was then conducted to aid the confirmation or refutation of these; objective tests to measure the patient's respiratory rate, heart rate, peripheral oxygen saturations, tympanic temperature, blood pressure, capillary refill time, Glasgow Coma scale, National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) and auscultation were conducted and found to be within normal limits. Pete did not have a history of any chronic lung conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma or bronchiectasis, so these were unlikely. Symptoms of cough can also be related to serious pathologies, including pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism (PE) or lung cancer. These potential differential diagnoses needed further exploration.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES OF A COUGH

Hospital admission due to a PE increased by 30% between 2008 to 2012, accounting for 28 000 hospital admissions in 2011 (British Lung Foundation (BLF), 2022). Despite this, deaths from PE decreased by 30%, accounting for 2% of deaths from a respiratory cause in 2012 (BLF, 2022). In 2021, male deaths due to pulmonary circulation pathologies within the local population and between the ages of 45–49 years accounted for 11 deaths (Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2023a). Nationally, in 2012, 2% of deaths were due to PE, while 25% were attributed to pneumonia and 31% to lung cancer (BLF, 2022).

Pneumothorax and PE were quickly ruled out in this case, as no other symptoms consistent with these pathologies were found (ie, no chest pain, dyspnoea, haemoptysis, reduced breath sounds on auscultation or hyperresonance on percussion) (BMJ Best Practice, 2023; NHS, 2023).

Lung cancer

Within the local population in 2021, the fifth most common cause common cause of death was lung cancer (NHS, 2022). Of males aged 45–49 years, there was a total of 15 deaths from lung cancer (ONS, 2023b). With these statistics in mind, and the potential signs and symptoms, lung cancer was a differential diagnosis that required further exploration (Cancer Research UK, 2023). Firstly, Pete had been a smoker since the age of 17 years, and evidence suggests 79% of lung cancers are linked to smoking (Cancer Research UK, 2018). Occupational risk factors were also present (prior employment in a sawmill); 13% of lung cancers are caused by occupational exposures (Cancer Research UK, 2018). Pete's age group is also significant, as guidelines advise that people aged over 40 years presenting with an ‘unexplained cough’ and with a history of smoking may be at risk of lung cancer and should be referred for an urgent chest X-ray (Cancer Research UK, 2023; NICE, 2023). ‘Unexplained cough’ is defined as symptoms or signs that have not led to a diagnosis being made by the healthcare professional in primary care after initial assessment (NICE, 2023).

Using the data and red flags identified, the fourth part of the CRC (processing information) was applied. Although lung cancer was the main concern, consideration had to be given to the possibility of the cough being post-infective. To differentiate between lung cancer and a post-infective cough, a chest X-ray is usually the first test requested (NHS, 2022). Chest X-ray, however, is not without risk, which lead to the application of the fifth part of the CRC (identifying problems and issues) (Levett-Jones et al, 2010). Although considered low-risk, chest X-rays expose patients to radiation that could cause cancer later in life (NHS, 2022). Public Health England (2008) states that the level of risk is 1 in 1 million. Therefore, weighing up the risks and benefits is essential. The ACP must ask themselves: ‘How useful are chest X-rays diagnostically?’

Chest X-rays and computed tomography scans

Although used as the first diagnostic test to check for lung cancer, a single chest X-ray may miss 25% of lung cancers (Turner, 2019). Authors have suggested that chest X-rays are not effective diagnostic tools, with some emphasising their harm (Bickley et al, 2021; Foley et al, 2021). One study encompassing 16 945 patients referred from primary care for a chest X-ray in the UK found that the most common presentation in all age categories was a cough (Foley et al 2021). Patients within the study with a normal chest X-ray did not undergo further computed tomography (CT) imaging, despite ongoing symptoms; a proportion of these were revealed to have lung cancer and experienced a subsequent delayed diagnosis (Foley et al, 2021). The authors concluded that a chest X-ray lacks sensitivity in the diagnosis of lung cancer; therefore, it is proposed that CT scans should be used as a first-line imaging tool (Foley et al, 2021). This conclusion is supported by Fu et al (2016), who, in their meta-analysis, found that, when using low-dose CT scans as a diagnostic tool rather than a chest X-ray, a greater number of patients with stage 1 lung cancer were identified, leading to significantly reduced mortality rates (confidence interval of 95%). Fu et al (2016) also report that, in some areas of the US, a low-dose CT scan is now the first-line diagnostic imaging tool to be used in high-risk patients. The new NHS lung cancer screening programme, introduced in 2023, supports these studies in the offering of low-dose CT scans for high-risk groups—namely, those in the 55–74-year age group with a history of smoking (East of England Cancer Alliance, 2023). This has yet to be established in Pete's area.

Most patients who are diagnosed with lung cancer (46.8%) are diagnosed at stage 4, mostly due to incorrect diagnosis related to the similarity of patient presentation to other respiratory problems, such as chest infections; a normal initial chest X-ray result; or a delay in presentation to primary care (NICE, 2024). Following a discussion with the tACP's clinical mentor, the decision to send Pete for a chest X-ray to exclude the possibility of cancer was made.

Clinical concerns were discussed with Pete, with an explanation provided of the potential diagnoses and the diagnostic benefits of undergoing chest X-ray, as well as the possible iatrogenic harm (radiation) and the limitations of chest X-rays as a definitive diagnostic tool (Levett-Jones et al, 2010). Pete consented to undergoing a chest X-ray, the goal of which was to aid the establishment of a diagnosis; therefore, action was taken by the tACP to order the investigation, which falls under the next part of the CRC (take action) (Levett-Jones et al, 2010).

Decision making

Decision making in clinical practice is an extremely complicated process, and some of the highest rates of error are found within the diagnostic process (Croskerry, 2018). Tay et al (2016) estimate that up to 75% of clinical diagnostic errors are related to failures in the clinical decision-making process, owing to lack of knowledge or understanding and inadequate information gathering. Kahneman (2012) theorised that there are two systems that our brains operate in to make decisions, dubbed System 1 and System 2. System 1 thinking is fast, intuitive, unconscious, automatic, effortless, with pattern recognition; it has no self-awareness, lacks control and incorporates 98% of our thinking (Kahneman, 2012). On the other hand, System 2 thinking is slow, deliberate, conscious, effortful, with self-awareness, and logic, incorporating the final 2% of our thinking (Kahneman, 2012). Clinicians often move between systems when making decisions (Kahneman, 2012; Tay et al, 2016).

Tay et al (2016) used a cognitive reflection test to analyse how 128 medical students think. The researchers found that students who solely rely on System 1 thinking processes displayed a higher error rate when answering the questions than those who fully engaged in System 2 thinking (Tay et al, 2016). When relating System 1 and 2 thinking to this case, the tACP identified that both types of thinking were used. The tACP's main role is to manage minor illness, with a cough being one of the most common complaints, frequently due to infection. The tACP, when using System 1 thinking and pattern recognition, viewed Pete's respiratory problem as most likely to result from infection. However, as a move to System 2 thinking began, with a more detailed exploration of the patient's symptoms and history conducted and a conscious effort made to obtain and process more information, a wider range of differential diagnoses presented themselves and the decision to refer for a chest X-ray was reached. If the chest X-ray suggested lung cancer, Pete would then be referred to a specialist under the 2-week wait pathway to confirm or exclude the possibility of cancer (NICE, 2024). He would also fit the criteria for a 2-week referral if lung cancer was still suspected, despite a negative X-ray (NICE, 2024).

Biases and decision making

When making complex clinical decisions, clinicians can rely on heuristics; however, this can leave them open to several biases that can impact their decision making (Thompson and Dowding, 2009; Walston et al, 2022). Heuristics are shortcuts that clinicians develop over time with experience and exposure to the same clinical situation, but they can leave clinicians open to diagnostic errors (Walston et al, 2022). This could explain why a chest X-ray was not previously requested or even considered. Norman et al (2017) report that heuristics are a key factor when errors in clinical decisions are made. Contrary to this, a review by Minué-Lorenzo et al (2020) reported that, in primary care, there is very little evidence to suggest that using heuristics causes clinical decision-making errors. This review, however, only included three out of a total of 48 studies that were based in a primary care setting (Minué-Lorenzo et al, 2020). Fernández-Aguilar et al (2022) analysed heuristics involved in the decision making for 371 patients presenting in primary care with dyspnoea. Three aspects of heuristics were assessed, (overconfidence, availability and representativeness); although frequently used, the rate of diagnostic error as a result of using these heuristics was not reported to be significant (9%) (Fernández-Aguilar et al, 2021). To reduce diagnostic error stemming from the use of heuristics, clinicians need to be more aware of their negative impact and use this knowledge to prevent them from adversely impacting clinical decisions (Vickrey et al, 2010). Use of heuristics leading to clinical error is referred to as a cognitive bias (Norman et al, 2017), and more than 100 different biases have been identified as impacting on clinical decision-making (Croskerry, 2013). Furthermore, both System 1 and System 2 thinking are open to influence and errors as a result of clinical biases (Norman et al, 2017).

Factors affecting clinical decision-making

Several factors can impact upon a clinician's clinical decision-making, the first of which are time constraints. In this instance, Pete was booked into a 10-minute afternoon appointment in a busy practice. A systematic review by Irving et al (2017), analysing over 28 million primary care appointments across 67 countries, found that appointment length had a direct impact on patient care. The authors found that short appointment lengths directly impact clinical decision-making, with most primary care clinicians feeling that it negatively impacts their decisions (Irving et al, 2017). In the UK, the average appointment time is stated to be 8 minutes, which, in comparison, is among the shortest in the Western world (Irving et al, 2017). Despite this, Irving et al (2017) found that appointment times did not affect the rates at which patients were referred for X-rays. Due to the implied negative impact that 10-minute consultation times have on patient care and the increased fatigue levels of clinicians, the British Medical Association (BMA) (2024) has strongly recommended that primary care practices should immediately move towards 15-minute appointment times to improve patient care. Similarly, an observational study, which analysed 4000 clinical encounters of 150 nurses in Scotland, found that fatigue directly impacted clinical decision-making; the report suggested that, after each patient is seen, clinical decisions become more conservative and less-resource efficient (Allan et al, 2019). However, in contrast, a cohort study carried out in Canada in an emergency department encompassing 87 752 clinical patient encounters found that rates at which patients were referred for investigative studies, such as CT scans, decreased towards the end of the shift when compared to the beginning (Zheng, 2018). Pignatiello et al (2020) found that decision fatigue is common among healthcare professionals and directly impacts on the planning and execution of a decision. However, it was difficult to establish the consequences of decisions made in this study, due to a substantial lack of documented results (Pinatiello et al, 2020). The authors suggest that development of theoretical models and further study of decision fatigue would be beneficial for the clinical environment (Pinatiello et al, 2020).

Decision fatigue is an important aspect to discuss, as Pete's consultation took place toward the end of a 9-hour shift. Although the impact of decision fatigue is very limited, it is clear from the evidence that it may affect clinical decisions, including the author's decision regarding whether to refer Pete for a chest X-ray or not. Allan et al (2019) suggest that decision fatigue is directly linked to the time elapsed since the clinician last had a break, with one way to reduce this being to introduce more regular breaks. This, in combination with the BMA recommendation (2024) to increase appointment time to 15 minutes, may reduce decision fatigue.

Reflection

The last two phases of the CRC are ‘evaluation of outcomes’ and ‘reflection on the process to aid learning’. To summarise, Pete had presented with a cough that had been ongoing for 3 weeks and had not responded to antibiotics; therefore, differential diagnoses were considered. The main concern was presence of lung cancer due to the red flags identified and lack of treatment response. The risks and benefits of chest X-ray were considered, and referral was made. The chest X-ray showed no abnormalities. The case history was discussed with the tACP's mentor prior to a consultation with Pete in a follow-up appointment 2 weeks later. At the follow-up, Pete reported resolution of the cough; he was given smoking cessation advice and agreed to a referral to a free local smoking cessation service. Safety netting advice was given regarding recurrence of symptoms. Following the consultation, the case was again discussed with the tACP's mentor, where it was agreed the cause of the cough was most likely viral; however, if the cough were to return, referral and/or further investigations, such as a repeat chest X-ray or spirometry, may be required.

Conclusions

Pete displayed several risk factors, which were identified from assessment and carefully considered. An element that was not considered prior to the writing of this paper was the value of and sensitivity of alternative investigations, such as a low-dose CT scan when assessing high risk patients with possible lung cancer. Despite this, most primary care clinicians are currently unable to refer for this investigation; however, in 2023, there has been a positive move within the NHS towards national lung cancer screening with low-dose CT for high-risk groups (East of England Cancer Alliances, 2023).

The tACP is keen to research this area further to see if there is evidence present to change local policy to benefit patients. Negative impacts on clinical decision-making were explored, and areas for improvement identified include increased appointment times, in line with BMA recommendations (2024), and regular breaks. The decision to refer Pete for a chest X-ray was within current national clinical guidelines (NICE, 2023) and associated with low risk. The tACP mentor played an important role in aiding reflection and learning. The outcome of the case was positive.