The standardisation of advanced clinical practice training is an important topic in the healthcare industry. In many countries, such as the Netherlands and New Zealand, advanced clinical practitioner (ACP) roles are separately regulated and are underpinned by standardised training programmes (Evans et al, 2021). However, this level of regulation and standardisation is somewhat lacking in the UK.

In attempts toward remedying this, Health Education England (HEE) in 2017 developed the multi-professional framework for advanced clinical practice and, although it specifically applies to England, it was developed in collaboration with relevant stakeholders across the UK and has been informed by existing advanced practice frameworks from the other three countries within the UK (Evans et al, 2021). This framework sets out the minimum standard for the safe and effective requirements for clinicians working at an advanced practice level to take on expanded roles within their scope of practice. It also recognises that introducing, developing, and supporting ACPs within an organisation requires good governance to embed advanced clinical practice in the workplace. To help strengthen governance arrangements for advanced level practice, HEE have also established a ‘Centre for Advancing Practice’, in which they recognise practitioners working at an advanced level through two routes, the accreditation of university education programmes and an HEE-recognition route that an individual can follow (HEE, 2023a). Regional faculties for advancing practice were later established to drive pioneering workforce transformation for advanced practice across England and help ensure the required standard for advanced practice was being met.

The faculties, of which there are seven, can do this as they are in a unique position to understand and address their region's workforce requirements, which enables them to identify workforce demand, commission high-quality education and training, optimise clinical training, supervision and assessment, and support communities of practice to drive ongoing development and support to improve patient care. (HEE, 2023b).

However, despite the significant input so far from HEE, significant variations around programmes, support and training still exist, particularly in areas where ACPs are less common, such as mental health.

In 2019, the NHS Long Term Plan, followed by the ‘We are the NHS: People Plan for 2020/21’, published their ambitious agenda to boost the development of advanced practice roles, particularly across professional groups in all mental healthcare delivery settings, primary care, and community services. These plans have been further reinforced in the recent update to the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2023).

The project

To help support this vision, the South Yorkshire Faculty of Advanced Practice, which is part of the Northeast and Yorkshire regional faculty, developed the Mental health, Community, and Primary Care Support Project in January 2022. The foundation of this project was derived from an earlier ACP MSc course support package, which was developed by HEE and a local higher education institute in 2017. This was later evaluated in 2020 by Smith et al (2020) on behalf of HEE and continued to advocate the need for support for tACPs in these specific areas to increase tACP retention and future growth.

The project employed three qualified ACPs from each area to support tACPs within their specialism, using their expertise and real-life experience of the ACP training journey to help support them through often uncharted waters. The offer to trainees included things such as (but not exhaustive of):

The leads would then contribute to reports back to HEE regarding the trainee's progression, to ensure the training funds were being utilised appropriately and continued to be paid. At the time of conducting the questionnaire, the project was well into its second year and had grown significant along with the relationships with the local NHS trust, employers and higher education institutes helping bridge the gap between practice and academia.

Aims

Unfortunately, we were told the project would end in March 2024 due to restructuring within NHSE and a lack of funds. As far as the authors are aware, this kind of support project does not exist in any of the other regional faculties. Thus, the authors asked the tACPs for anonymous feedback about their interactions with the project via an emailed Microsoft Forms questionnaire. This format was used as the participants had already given their consent for email correspondence from the project and the form used would be familiar, as it was similar to the feedback forms used after the project's education events.

Methods

A questionnaire was generated using Microsoft Forms, with response choices including multiple choice, rating scales and free-text. The questionnaire covered the following areas, which will also be used to guide the results section:

The free text was analysed for themes by the author (CJ) collating common words. A second checker also did the same and the lists were compared and agreed.

Results

A total of 64 people responded to the questionnaire invite and were asked what their job role or title was. Of the 64 respondents, 43 said they were tACPs, 10 were ACPs, 5 had other job titles (community matron, pharmacist, practice nurse) and 5 did not state what their job titles were.

Contacts with the project

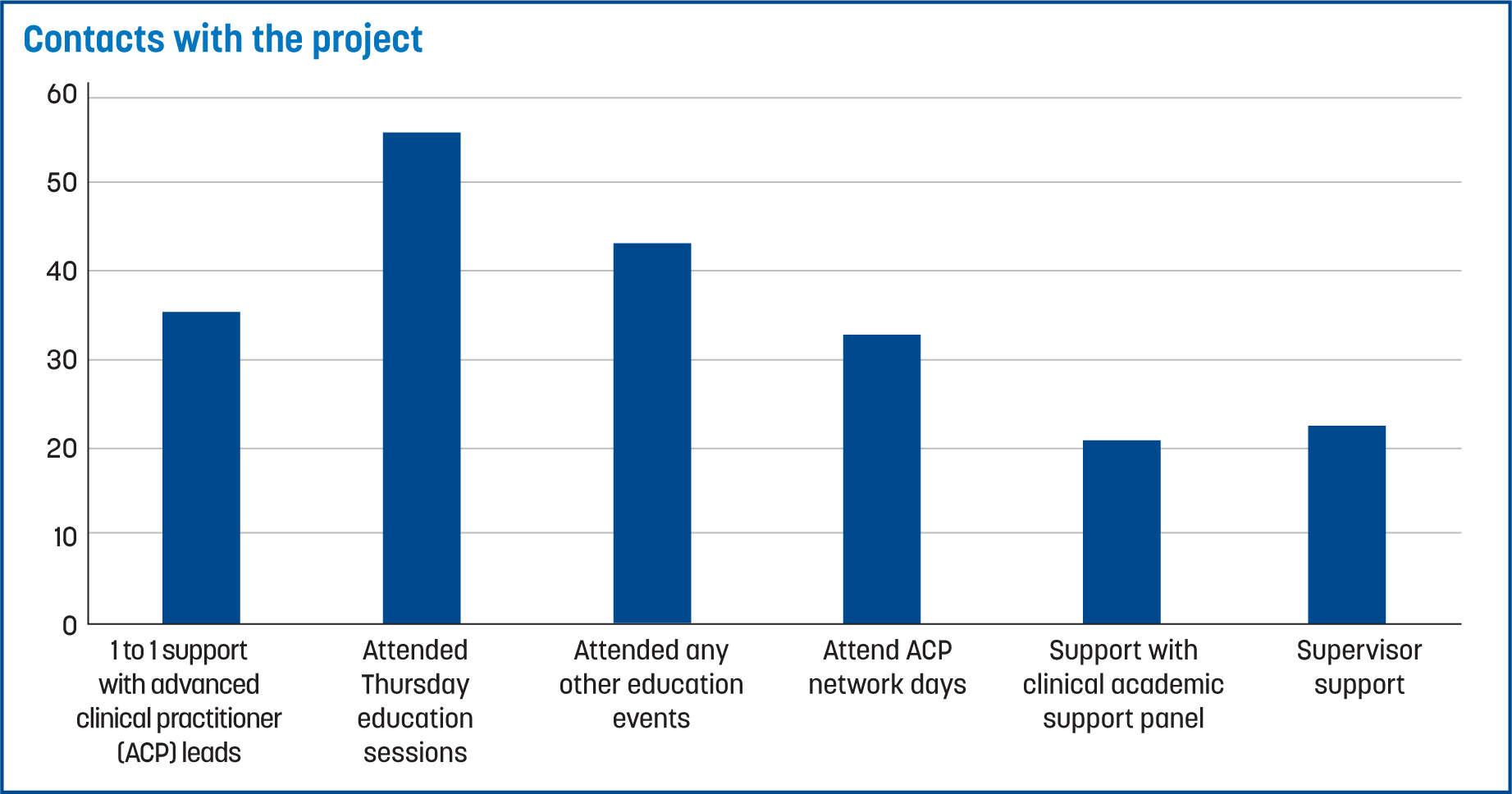

Most tACPs had contact with the project several times, with 22 trainees having contact up to 5 times and 39 trainees having contact more than 5 times. One tACP responded no contact, and two reported contacting the project once. The following graph (Figure 1) details what the contacts were about, with most respondents feeding back they used a mixture of online and meeting in person for this contact (n=39), while some (n=25) respondents used teams alone and some (n=9) met in person.

The advanced clinical practice leads

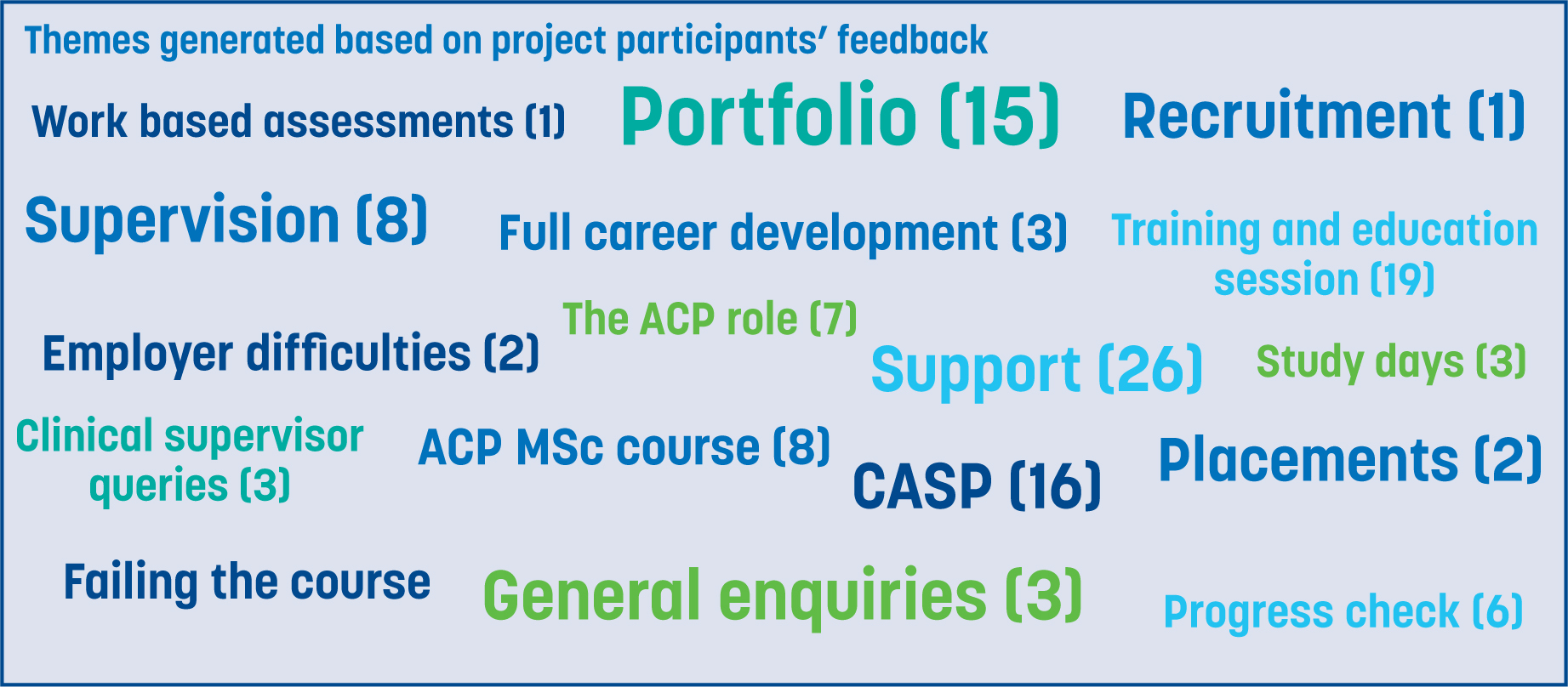

A total of 60/64 respondents reported they had met with an ACP lead individually. Up to 37 reported this was through a mixture of in person and online, while 18 met just online and 6 just in person. When asked to briefly describe what the contact was about, 59 tACPs responded; themes were then generated in relation to the number of times each aspect was mentioned (Figure 2).

When asked how useful this contact was on a scale of 1 to 5 (5 being ‘very helpful’ and 1 being ‘not very helpful at all’):

A total of 58 respondents felt they could not have accessed this support elsewhere; 3 stated that they felt they could.

Education and learning events

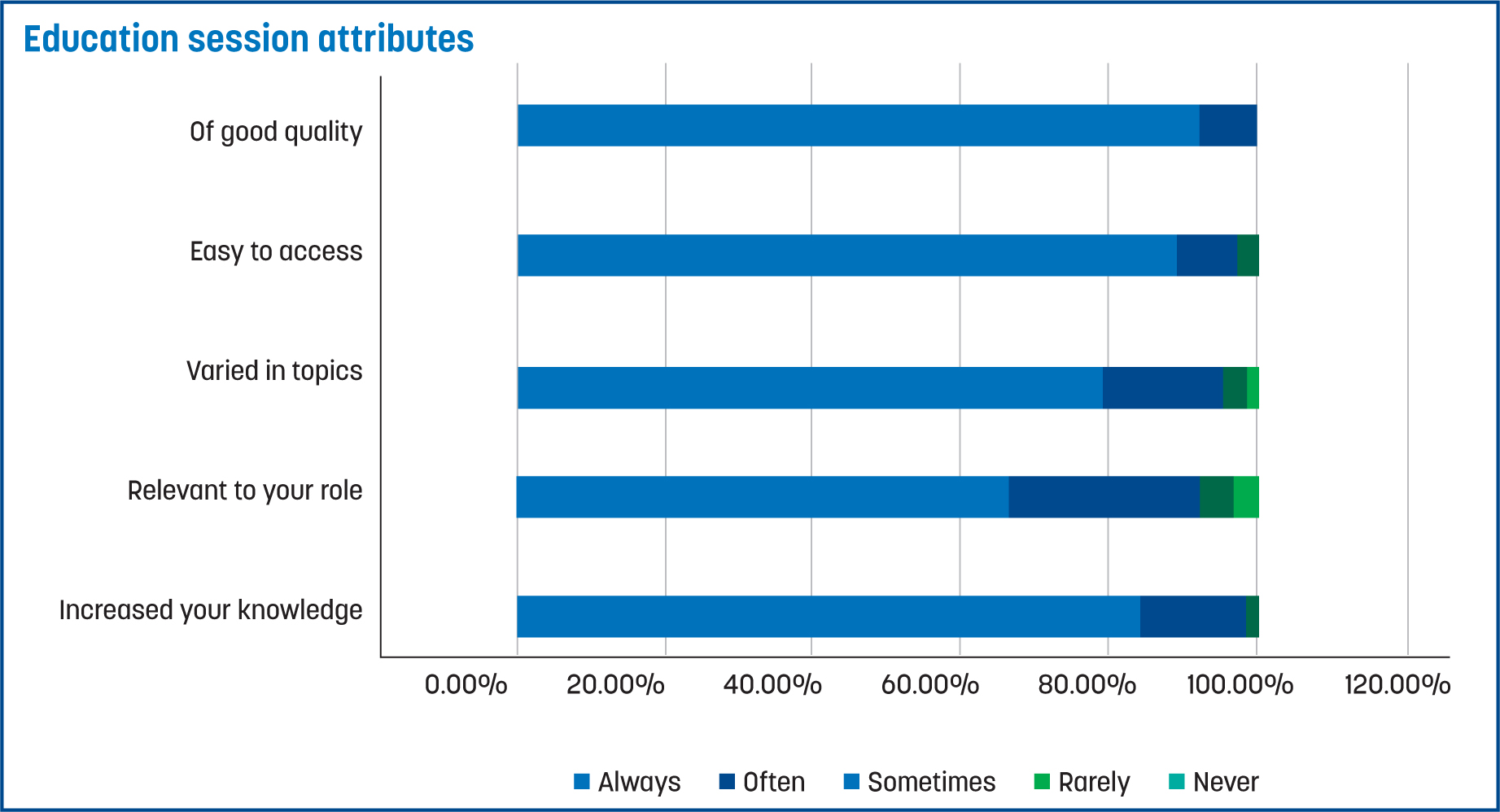

Two respondents reported that they had never attended an education event and 5 reported they had done this just once. However, the majority reported multiple attendance, with 21 respondents reported attending education sessions two to five times, and 35 reporting to having attended over 5 times. The participants were also asked to rate several attributes about the education sessions. These responses are displayed in Figure 3.

Advanced clinical practice network days

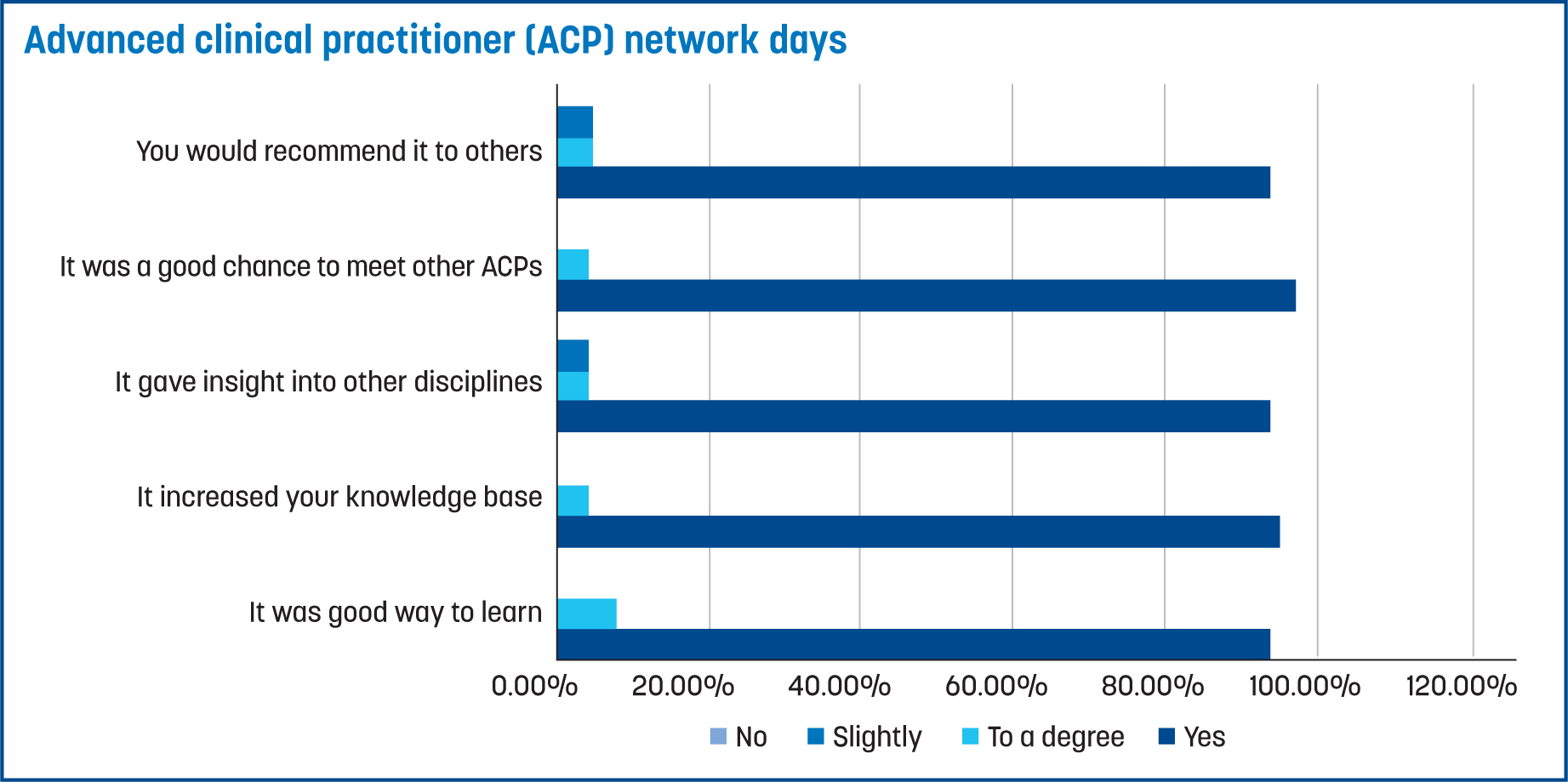

Some 28 of the respondents advised that they had attended an advanced clinical practice network day; a further 17 advised they would like to. A total of 14 respondents had not attended, and a further 3 stated that it was not something they would want to do.

The participants were then asked to comment on several attributes applicable to the advanced clinical practice network days. The responses are documented in Figure 4. All 28 clinicians who had attended an advanced clinical practice network day responded to all the survey's questions.

Other contacts

Participants were asked if their supervisor had had contact with the project; 37 reported that they had and 23 reported they had not. A total of 30 participants reported that they had contacted the project regarding CASP reviews, while a further 33 participants had contacted regarding their portfolios and work-based assessments. Participants were also asked if they felt the project had helped their ACP training; the majority reported ‘yes’ (55) and only four reported ‘no’.

Finally, participants were asked how important was it that this type of support from the faculty project is made available for future tACPs. They were asked to rate from 1 (‘not very important’) to 5 (‘very important’). A total of 54 trainees responded with a rating of 5, three responded with a rating of 4 and one responded with a rating of 3. Only one respondent chose the rating 1.

Discussion

Results from the questionnaire suggest that the project fulfilled a need that trainees had, specifically regarding the experience and navigation of the trainee ACP journey, and the demand for specific tailored education events.

The ACP leads appeared to be a constructive and helpful asset to the tACPs. This may be because they had all previously completed the advanced clinical practice MSc course, had experience keeping portfolios and were working as qualified ACPs in clinical practice. Through this, they were able to give help and insight into areas that are not on university websites or in textbooks. The leads could give the ‘real life’ example of what things meant, tips to make their journey easier and, more importantly, demonstrated that completing the MSc degree ACP training is possible, which encouraged the trainees. The project also gave trainees a place where they could talk confidentially about the difficulties they were experiencing at work or in university, and receive support and direction from people who understood the fuller landscape encompassing all parties involved.

As mentioned previously, most respondents (58) reported they did not feel they could get the level of support provided by the project anywhere else. This may be due to the limited number of ACP lead roles currently operating in South Yorkshire, which, in turn, has limited the number of those available to mentor trainees. Good mentorship has been shown to increase the attainment of clinical skills, as well as reduce feelings of isolation, which new trainees are likely to experience (Reynolds and Mortimore, 2021). Unfortunately, many ACPs, especially in primary care and new emerging roles, often work alone.

The project coordinators have been able to evolve and respond to the feedback with a relative lack of restriction, which has enabled them to tailor learning events around the needs of the trainees; of which, many encompassed a mix of theory, experience sharing and a practical aspect, such as simulation to help tACP's understand the ‘theory to practice’ link. Unfortunately, tight university schedules often do not lend themselves to such practice, although it appears very much wanted.

For countries outside the UK, projects like the one discussed in this article could easily be replicated in some form, as the identified need underpinning this work is simple; tACPs value support from qualified ACPs who have experienced the same journey they are on.

Ideally, major stakeholders that are currently developing the ACP workforce would fund local support initiatives aimed at the recruitment and retention of ACPs, and replicate the project discussed. Moran and Nairn (2018) analysed role transition for ACPs and identified appropriate mentorship, alongside clinical supervision, supported development and formal education programmes to be essential for tACPs, both pre and post-qualification. However, several countries have differing interpretations on the perception of the ACP role, the route to obtaining the role, and how it should be implemented; these features limit the repeatability of this project (Unsworth et al, 2022).

Mentorship programmes may provide an alternative way to access the support of qualified ACPs; these could be established via several routes, including higher education institutions using their alumni. A similar concept could be adopted by large health care providers, utilising their own qualified ACP's to create their own internal support programme. In the authors' experience, qualified ACPs are often willing to support trainees and pass on their learning.

This project has recently begun working with a local higher educational institution, which recognises the value of the approach discussed in this article, to look at ways of bridging the existing gap between tACPs and ACP leads. Unfortunately for the trainees of South Yorkshire, the mental health, community, and primary care advanced practice support project came to an end in March 2024 due a lack of funding.

Limitations

As this article describes the feedback given by some professionals in advanced practice accessing a unique support project, the generalisability of its findings is limited. It also must be acknowledged that six out of the 64 respondents did not have tACP or ACP job titles, and it could not guarantee they were from an advanced clinical practice background.

Conclusion

ACPs and tACPs seem to appreciate support and education from other ACPs due to their shared experience of the advance practice training. Unfortunately, this is not widely available to many (especially in primary care and mental health). However, projects such as the one discussed in this article could help fulfil that need and help more clinicians reach their goal of becoming ACPs.