In the UK, a cancer diagnosis is made every 2 minutes, with around 375 000 new cancer cases reported every year (Cancer Research UK, 2023). Cancer predominantly affects the elderly, with 36% of patients being aged 75 years and over when diagnosed (Cancer Research UK, 2023). With the increase in public health promotion and screening, there has been a rise in earlier, potentially curable diagnoses, which may require combined modalities of treatment. Increased survivorship requires care for those with longer-term complications from cancer treatment (Royal College of Radiologists (RCR), 2021). While advances in personalised treatment, systemic anti-cancer therapies (SACT) and technologies in radiotherapy have had a positive impact on patient outcomes, resourcing and delivering these advances remains a challenge for the NHS. Moreover, pressures in the service restrict progress and its ability to rise to the challenges; reforming the workforce is vital to ensure cancer services thrive and operate as effectively as possible.

There are several health professional roles across the non-surgical oncology service. Each respective role incorporates a skillset that has a positive impact on patient experience and outcomes. However, workforce numbers are depleting across all the professions:

While there is a desire and need to increase clinical and medical oncologist staff numbers, workforce reform plans provide the opportunity to support service provisions by expanding the roles and numbers of advanced practitioners (APs) across the speciality. In addition to career expansion, there is growing evidence that such roles often offer significant improvements in team working, quality and safety of care (Khine and Stewart-Lord, 2021).

Role progression towards advanced practice is not a new concept and has been part of the NHS since the earliest implementation of the role in 1990 (Leary and MacLaine, 2019). Since its inception, advanced practice roles have developed at pace, usually locally or regionally as service has required. However, the pace of their development has resulted in lack of standardisation across the country and variations in roles, responsibilities and training, as well as inconsistency around banding and pay. The multi-professional framework (MPF) for advanced clinical practice in England (HEE, 2017) established 38 capabilities across the four pillars of practice (clinical expertise, leadership and management, education and research) to provide a benchmark of practice across the professions; however, education and training specific to non-surgical oncology was absent.

In 2019, a local service review in Northern England highlighted how the difficulties in recruiting consultant clinical and medical oncologists into post posed a significant risk to service provision (RCR, 2022). A previous in-house service review in critical care and emergency medicine in the region acknowledged similar concerns and, in response, an advanced practice pathway to support these services had been implemented and shown to be successful. Therefore, with the support of local NHS education and alliance groups, a similar project to develop a training programme for APs in non-surgical oncology was developed; the project was launched and commenced in January 2020.

This non-surgical oncology advanced practice (NSOAP) curriculum framework aims to produce APs focused on delivering patient-centred care (pre-, during and post-treatment), who possess the specialist expertise, knowledge, skills and behaviours required to support and manage the needs of complex cancer care within their scope of advanced practice. It supports the development of APs who are flexible in shaping the service through evidence-based practice, adapting to changing needs, assimilating and incorporating new evidence rapidly and promoting an advanced skill mix. Trained APs would provide leadership, training and supervision of other healthcare professionals, as well as managing service demand.

The primary objective of this curriculum is to produce APs who, at completion of training, will be equipped with the transferable skills that allow them to: manage patients or treatments; practice with minimal supervision within a defined scope of advanced practice in cancer care; adapt and respond to the needs of the local population, to contribute to service development now and in the future.

Aims

This article aims to assess the relevance of the curriculum framework for APs in non-surgical oncology and examine its associated implementation issues in Northern England. The objectives are to:

Methods

This qualitative study was designed to examine the perspectives of professionals currently in training as APs, working as APs or working with APs, using the NSOAP curriculum framework. The researchers used a phenomenological approach, which focused on the lived experience healthcare professionals had using the framework. Ethical approval was gained from a local university (approval code: ER45712144).

Those who were in a trainee advanced clinical practice post, supervising advanced clinical practitioners, qualified advanced clinical practitioners or working as associated team members were asked to review the NSOAP curriculum framework and then attend a 30-minute semi-structured interview to evaluate the framework and its implementation. The questions used for this evaluation were built upon a phase one study that investigated advanced practice in therapeutic radiography (Stewart-Lord et al, 2020).

A purposive sampling approach was adopted by requesting the participation of those working in the locality; using this sampling approach allowed a richer collection of data from a defined population group. A total of 14 participants were interviewed to gain their thoughts and views on AP education and the NSOAP curriculum framework. The sampling strategy aimed to include a variety of participants, such as trainees APs, qualified APs, medical and non-medical consultants, and clinical supervisors.

A participant information sheet and consent form were provided to all potential participants directly via email, as they were approached for interview. All confidential data were securely held by a local higher education institute under a data management plan.

The interviews were completed virtually (using the Zoom platform), recorded, and transcribed; field notes were also collated. The recording platform was password protected and used the waiting room function to ensure the conditions were controlled. Interview transcripts were reviewed by the research team. Thematic analysis was used to critique the data using Braun and Clarke's (2006) approach, as stated in Maguire and Delahunt (2017). Individual transcripts were coded independently, collective themes were reviewed, discussed and later agreed. An independent peer reviewer also completed a sense check of the transcripts for agreement of final themes.

Results and discussion

Four overarching themes emerged from analysis of the data:

Advanced practice role description

All collected data clearly identified that the role description of those working at an advanced level of practice was important and that it should clearly define what working at an academic level seven (MSc) across the four pillars of practice entailed. This provided reassurance that the national MPF guidance on advanced practice was being recognised in the clinical practice setting.

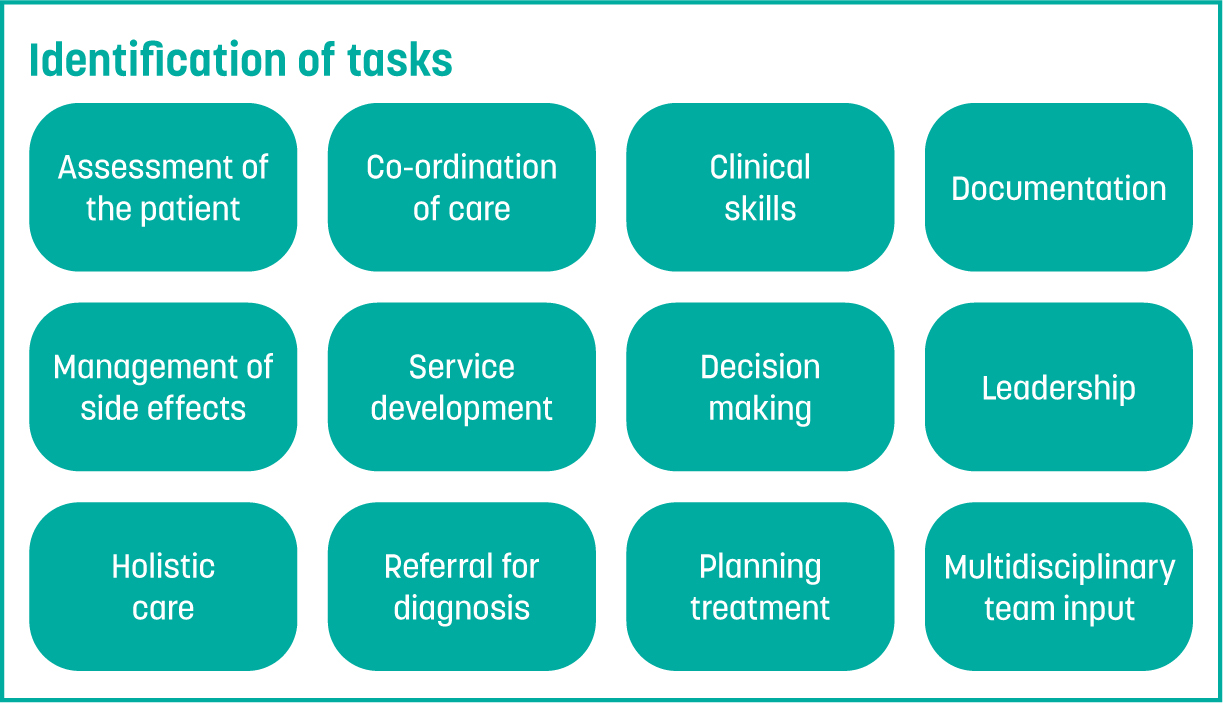

Those extending their practice to advanced level should also gain additional skills across cancer care, with the aim being to work with indirect supervision once qualified. There was a lot of discussion around which ‘tasks’ would be classed as ‘advanced level’, although it should be noted that task sharing can be at different levels of practice. Tasks identified by the participants as part of the AP role are shown in Figure 1. Three of the pillars of practice are clearly identified in this task list: clinical practice, leadership and research. However, the educational pillar was not identified. It was also surprising to see that the level of autonomy and responsibility of the role was not recognised.

Another aspect in this theme that was considered were the differences between advanced and consultant-level practice. This was defined by the participants as independent prescribing, responsibility for the whole patient pathway and the autonomous management of the patient from referral by participants. However, this does not align with national guidance on consultant level practice (NHS England, 2023a).

The NSOAP curriculum framework

Overall, the curriculum framework was welcomed by all participants. The framework was considered comprehensive and provided structure to the education and training of trainees. Participants acknowledged that it helped standardise role development and provided clear guidance on requirements. The specific nature of the framework was also considered succinct and efficient, with specific education and training relevant to their role. It was also considered to be effective at providing the level of knowledge and skills required to work in non-surgical oncology at this level of practice.

Barriers to advanced practice

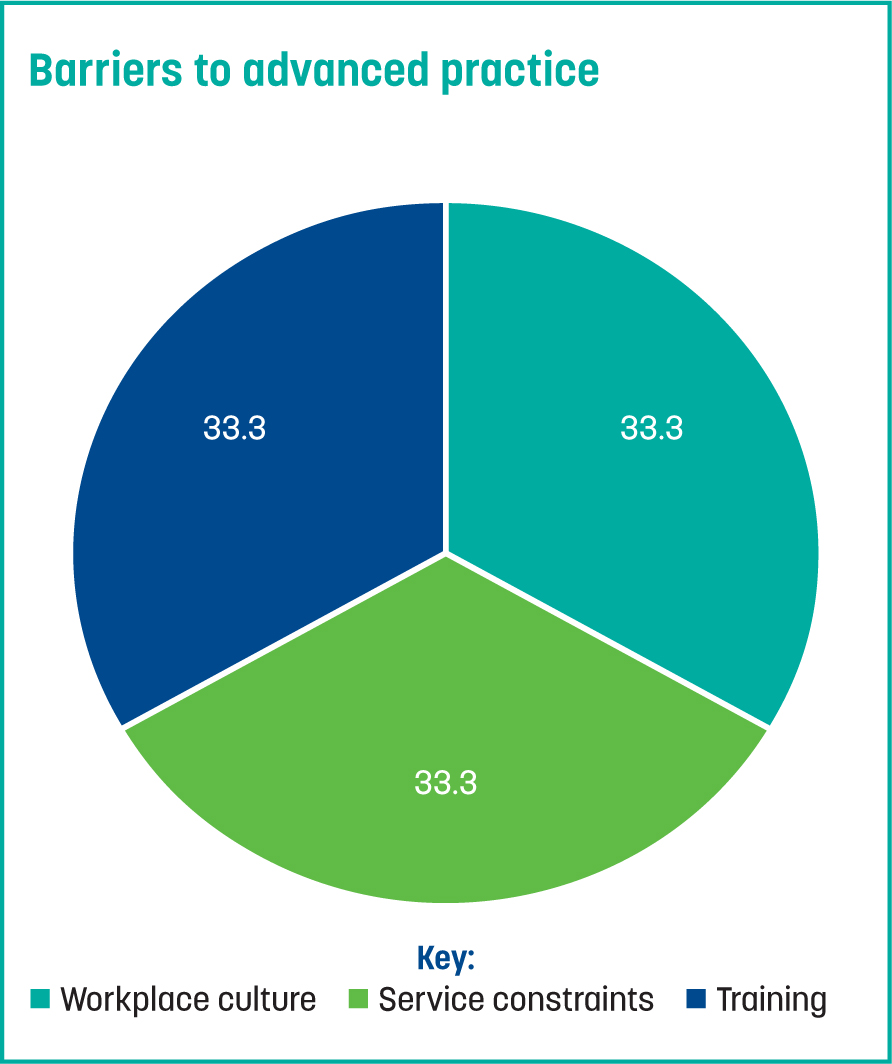

As part of the research, it was important that the barriers to the implementation of roles and the curriculum framework were considered. Three sub themes were identified (Figure 2). These are discussed in greater detail later in the article.

Enablers to advanced practice

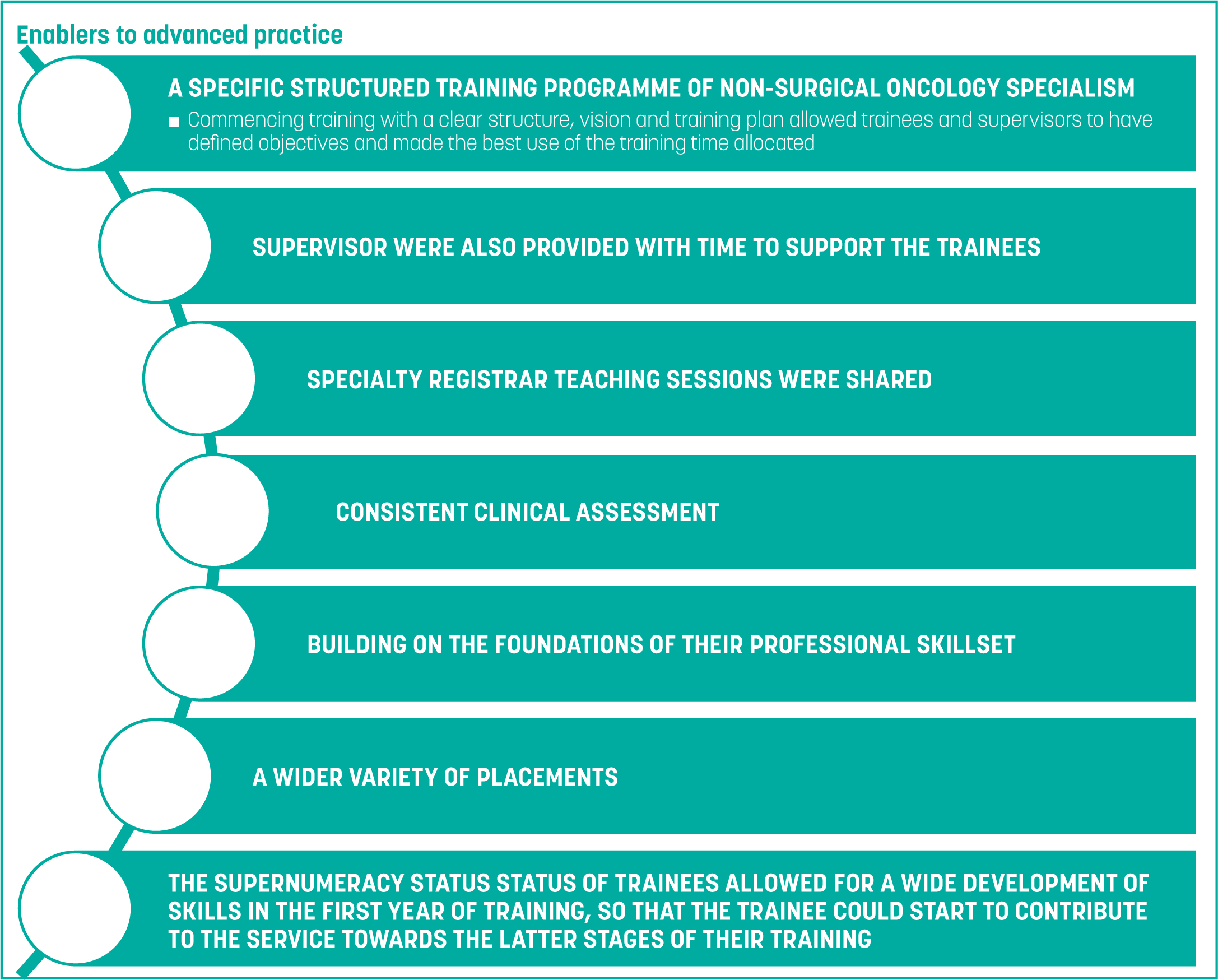

The data uncovered several positive enablers to the use of the NSOAP framework (Figure 3).

Advanced practice role description

AP roles are often developed as a result of the shortfall in oncologists; therefore, those training and working as APs will undertake tasks previously completed by oncologists (Khine and Stewart-Lord, 2021) and be tasked with innovating and diversifying the methods of service delivery. In this situation, APs may have more appropriate professional training, knowledge and skills to deliver aspects of the service, the completion of which provide opportunities for career progression and personal development. The present study's participants frequently defined the roles by the tasks to be completed; however, the emphasis on defining a level of practice has now moved away from task-orientated roles and onto the level at which the tasks are completed, to aid in the definition of enhanced, advanced or consultant practice.

It was also noted that advanced practice was still seen by some participants (mainly trainee APs) as taking on the role of a doctor, with the goal being to reduce their workload in a synergistic relationship that was beneficial to peers:

‘My role is going to come in to help to reduce that workload from the consultants' day to day.’

‘Non-medical practitioners, who are training to a level to support consultants in delivery of practice…’

These posts, in part, have historically been developed to meet demands caused by shortage of medical staff. However, the researchers have recently seen a shift occur, with the AP roles now being viewed as a progression opportunity for staff and a chance to enhance patient care, with the inclusions of differing skillsets and perspectives:

‘I would hate for these to be service delivery roles, so I think it's great that you're thinking about how they could actually improve the service.’

The importance of career progression and the building of profession specific skills should be more widely embedded in practice; this notion is supported by the NHS England (2023b) Long Term Workforce Plan, which aims to train, retrain, reform, support and grow the clinical workforce. It is evident from the gathered data that there are other secondary issues surrounding the AP role:

These issues are concerning, given that the scope of practice provides the boundary of care provision by the AP and the requirement for referral or support. This is one of the most important clinical governance documents and responsibility for the currency of the document should be considered by both the trainee AP, the qualified AP and the management of the wider service:

‘It has been such a slow start in. No one sort of knows exactly where it's going to take shape. And in that first [few months] I did think, maybe I have made a really big mistake.’

Adequate educational supervision was highlighted as a concern, with time allocated for supervision not added to the supervisor's job plan:

‘Some are really thorough. Nursing ACPs they are getting really good support, but for us in radiotherapy, it's ad-hoc and not structured. That is not a criticism of the clinicians… it's how they fit it in to their job plans because they're already stretched.’

Recent work by the Centre for Advancing Practice around supervision has provided checklists, self-assessments and wider resources to support the implementation of supervision for advanced practice. Wider consideration of the impact of this work is needed.

The NSOAP curriculum framework

The participants' responses highlighted areas that required further development, and the framework's impact; for example, the wider consideration of the SACT capabilities, specifically around prescribing chemotherapy. This will help to support the development of practitioners into the advanced practice space, as they prescribe and assess toxicities of SACT treatment. Further additions to the capability in practice (CiP) are required for this to be addressed. However, it should be noted, CiPs are high-level learning outcomes and their underpinning details are highlighted in the descriptors, supported by the academic and clinical training:

‘Common oncology CiPs was whether there was enough background knowledge for everyone in terms of SACT.’

‘I think they are a bit light and generic…they need the broad brush, then tumour specific.’

‘I think probably immunotherapy and standard SACT need to be there in a bit more detail.’

The issues with clinical skills taught in academic education were also discussed. Often, the generic clinical skills taught as part of MSc-level education for some advanced oncology roles lacked some skills that are required. For example, a module on clinical skills may not offer taught resources on breast examination, which is vitally important to working with patients with breast cancer:

‘I know that ACPs have struggled with the clinical skills teaching that they've had, and you know, they feel anxious about applying it in clinical, and perhaps haven't got to practice it.’

‘It's not relevant to some bits [of their work], or they don't know it [it hasn't been taught].’

It was suggested that it would be beneficial for education institutes to review their clinical skills modules that related to advanced practice and ensure that a clear outline of what would be covered is provided to their trainee practitioners.

Onco-geriatrics was highlighted as an example of a module that would be beneficial to include in the curriculum. As cancer is a disease more common with increasing age and the highest incidence is seen in people aged over 75 years, knowledge of frailty would help to inform treatment plans. A greater awareness and potential treatment for co-morbidities related to frailty allows for more effective treatment pathways and a more constructive experience for the patient:

‘I think if you did [include frailty] you'd be ahead of the game because there's almost a speciality evolving of onco-geriatrics, because so many patients are now getting treatment because of all these different drugs, we've got people with a better toxicity profile.’

Barriers to advanced practice

Barriers to the implementation of roles and the curriculum framework were a significant theme reported in the data. Three sub themes were identified: workplace culture, service constraints and training.

Workplace culture

Participants identified that there was resistance to change in the workplace, either by their peers or the professional hierarchy across the health service. It was also reported that there was a lack of engagement in progressing the service. This was particularly evident with allied health profession roles, where participants felt their unique skills did not have the respect and recognition across the trainees, practitioners and supervisors:

‘Often, I am always compared…obviously they've got a nursing background and I've got radiotherapy. But it is still very different…they've obviously got incredible skills and good clinical knowledge, but I don't think people [are aware] of what radiotherapy actually involves or our skills.’

Service constraints

Participants highlighted concerns regarding the redeployment of senior staff as ACPs in clinics away from the base team, and the impact this can have on the service and the practitioner. In an already stretched workforce, allowing the most experienced practitioners to progress into new areas can be difficult, especially when the time for training and supervision is so precious.

The trainees following the curriculum framework were afforded 100% (off the job) training time in the first year, to allow for a speedier return on practitioner development. This challenged practitioners, as they observed their peers struggle with the day-to-day service, while they had other commitments for training. Many sacrificed their training time to support their patients and peers. However, if this approach becomes normalised, practitioners may miss out on training opportunities and undermine their progression in their AP role:

‘But it's quite hard to say “no”; whereas I know that a lot of the other people in our university group are completely supernumerary, so it seems to be a lot easier for them.’

‘I was definitely naïve coming into this role.’

A lack of adequate job planning for the four pillars of practice demonstrated a lost opportunity to maximise the wider positive impact APs can have on the service. This should be planned effectively to gain the greatest benefit. There was also a lack of administrative time allocated for the role of the AP; this further highlighted the need for job planning to acknowledge the administrative burden of patient care.

Training

A lack of communication between educational institutions and clinical practice was reported to have caused significant issues for some ACP trainees. Many of those using the apprenticeship pathway for their academic development felt better communication pathways would enhance their training:

‘I do think there is a little bit of a disconnect [between the] university [and] department…people in the department, who you are working with, who haven't really got an understanding of what the role is, who perhaps don't get it as much.’

The need for further guidance on responsibility for assessing trainee competence was highlighted. Who was responsible for deeming a trainee to be competent needed clarification. Since these data were collected, additional guidance on workplace supervision has been published (NHS England, 2020) and will be embedded in the definitive version of the curriculum framework.

A clear and realistic scope of practice should be provided from the outset of training and reviewed every year with all competency training, to reaffirm currency or action plan and update for governance purposes. Some trainees had roles that were covering numerous tumour sites, which is difficult to develop to advanced level practice:

‘[I felt] very overwhelmed and a little bit intimidated.’

The scope of practice provides direction to the individual in a time of change. Making the change from having been an experienced practitioner to training in a new role, where the individual is a new learner, can be daunting. Providing support via governance and supervision helps the trainee throughout this transition.

Enablers to advanced practice

The user-friendly nature of the curriculum framework supported the development of trainees in a clearly defined way, building the trainees' resilience throughout their training pathway. The additional support of funding and training time had a significant impact on the successful implementation of the framework:

‘[Important] within these ACP roles, especially in radiography, is the pastoral supervision and the actual psychological supervision.’

A variety of work-based assessments are highlighted in the framework, covering all four pillars of practice. Although these assessments are frequently used in medical training, they are less familiar to other healthcare professionals:

‘I think the trainees need educating on how to use them (workplace based assessments) and not be scared of them. They can do them all the time and link to a portfolio to show development.’

Frequent work-based assessments allow for consistent review of knowledge, skills and behaviours to show development of the trainee. It is also important that these assessments are embedded with critical reflection in action to develop reflective practitioners at this level of practice. The consideration and discussion of next steps in learning enables efficient development and progress.

Training time can be difficult to implement by the trainee, supervisor and the service. However, the impact and progression of the trainees can be expedited when it is embedded fully:

‘I could learn the task within the framework of the module, but by doing them at the very beginning, I was able to then spend the remaining training period perfecting and moving from being task-oriented, to just being proficient, confident and an expert in those areas.’

In addition, the inclusion of additional support from peers in the WhatsApp group and the wider educational training delivered in the region also enabled the progression of trainees in their role.

Limitations

A robust methodological approach was undertaken to increase reliability of the study's outcomes. Limitations to the project were kept to a minimum by ensuring that members of the working party undertook the project and data collection, but not the lead, to reduce a power imbalance. To ensure consistency of data collection, the same researcher led the interviews. It is recognised this may have introduced unconscious bias, which is a potential limitation of the study. To redress this, and improve reliability and validity, the analysis was completed individually by both researchers (MC and RK) and then by a researcher (DH) not involved in the study, to ensure parity of the themes.

Conclusions

This local evaluation provided an opportunity for formal consultancy from those using and impacted by the curriculum framework when it was implemented in Northern England. It was evidenced that this curriculum was new, the trainee positions were still being embedded in service and some lack of understanding was present. Key considerations that will inform the next version of the framework and its implementation include: the further education on advanced practice to the wider service; consistent governance to protect the patient, practitioner and service; further clarity on the SACT capabilities in practice; inclusion of frailty; review of clinical skills; job planning for supervision; and wellbeing support. On the completion of the next draft, a national consultation project will be developed before endorsement as a credential with the Centre for Advancing Practice in England.