This service evaluation reviews the effectiveness of a virtual fracture clinic (VFC) in a major trauma centre (MTC). Fracture clinics are finding it harder to match capacity to demand due to growing attendances at emergency departments (EDs). Recent model hospital data shows a 10% increase in ED attendance over the last 10 years (Department of Health and Social Care, 2021). Healthcare costs in the UK are a significant burden to the taxpayer, with it estimated that they account to between 2 and 18% of GDP (World Bank, 2023). The NHS is currently facing unprecedented challenges, including an ageing population, a shortage of doctors, more complex and demanding medical treatments, and elevated patient expectations (Pickersgill, 2001). In 2023, the NHS performed 124.5 million outpatient appointments in the UK, a 31.7% increase from the previous year; 25% were new referrals and 75% were follow-ups, with trauma and orthopaedics (T&O) accounting for 6.7 million appointments (7%) (Parliament UK, 2023). Growing patient numbers, lengthy delays and stressful environments, for both service users and staff, have meant that the traditional models of care have become unsustainable (Wilson and Roy, 2014), and have contributed to high non-attendance rates and poor patient and staff satisfaction (Harrop, 2001).

To address these issues, Glasgow Royal Infirmary first piloted and established the VFC model to improve patient care for people with orthopaedic injuries (Jenkins et al, 2016). The VFC is a multidisciplinary clinic where radiographs and patient notes are reviewed by an orthopaedic consultant and, in this case, an advanced physiotherapy practitioner. Following review of the notes and radiographs, a decision is made on the management plan for each patient. The patient is contacted by the clinical team, who have a detailed discussion with them about their case and ongoing management. All patients are given a ‘helpline’ contact number should they have further questions or concerns.

In the first year of its inception at Glasgow Royal Infirmary, over 50% of patients were discharged from either the ED or the VFC, which reduced the financial burden of further face-to-face attendance and its associated costs (Jenkins et al, 2016). This system has been evaluated as safe and cost-effective, and has been shown to reduce costs per patient. The overall cost per patient of the VFC pathways is only £22.84, which is less than the £36.81 per patient that comes from engagement in traditional face-to-face fracture clinic pathways (Anderson et al, 2017); the traditional pathway is, on average, 61.2% more expensive than the VFC pathway. Further research has shown that the VFC produces good patient satisfaction scores over the medium term (Brooksbank et al, 2014; Jayaram et al, 2014; Vardy et al, 2014; Gamble et al, 2015; Jenkins et al, 2016; Anderson et al, 2017; Bellringer et al, 2017; Bhattacharyya et al, 2017; Brogan et al, 2017; Holgate et al, 2017; McKirdy and Imbuldeniya, 2017; Thelwall, 2021; Thomas-Jones et al, 2022), with clear benefits for patients demonstrated. These include:

Despite these established benefits, there is a deficit in research evaluating their long-term results (Thelwall, 2021). The authors for this article conducted a mixed methods review that looked at both quantitative and qualitative outcome measures of their VFC over an 8-year period. This is the largest longitudinal study of a VFC to date and the only study that examines a VFC that is held in an MTC. As the VFC at our site (Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust) as commenced in 2014, 2014 is the earliest point that statistical analysis has been gathered from.

Aim

This study aimed to explore the benefits, challenges and outcomes of a VFCs over a 8-year period. The objectives were to evaluate the:

Methods

A mixed-method longitudinal observational study was conducted and reported in accordance with the SQUIRE2.0 guidelines, to ensure transparency and improve the data and outcome quality; title; abstract; problem description; available knowledge; rationale; specific aims; context; interventions; measures; analysis; results; summary; and interpretation (Goodman et al, 2016). Data were compared annually from 2014 to 2022.

The study was conducted in a MTC that had 32 orthopaedic consultants working in it and received approximately 5000 fracture cases per year. The VFC ran on a Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and was staffed by an orthopaedic consultant and physiotherapy advanced practitioner. The model of review is as described by Jenkins et al (2016).

An advanced physiotherapy practitioner (APP) was employed to lead and manage the VFC from its inception. The APPs conducting the VFC were drawn from both the ED and fracture clinic staff, which collectively ensured there was a sustainable pool of well-trained clinicians at hand. Many staff work in both the ED and fracture clinic; this factor has helped improve communication, flow across directorates and patient pathways (Kodomuri et al, 2021).

Patients attending the ED with common orthopaedic injuries were treated and discharged on the same day or referred to VFC. Except for the first year (for audit purposes), a total of six injuries did not get referred to VFC: fractures of the fifth metatarsal base; fifth metacarpal neck; undisplaced radial head; paediatric clavicle; paediatric torus of the wrist; and mallet injuries of the finger. As identified in the Glasgow model, these injuries were discharged from the ED with protocol leaflets (Brooksbank et al, 2014; Vardy et al, 2014; Gamble et al, 2015; Bhattacharyya et al, 2017; Brogan et al, 2017; Kodomuri et al 2021). As a result, they were are not included in the discharge statistics. The VFC process is summarised in Figure 1.

Discharge rates

Rates of discharge were obtained from the trust's business informatics department.

Re-attendance rates

A sample of convenience was used over a 2-year period from November 2014 to October 2016. The cut off was patients reattending the ED with the same injury within 8 weeks of VFC discharge.

A second follow-up review was undertaken from November 2019 to October 2021. Data were drawn from the trust's electronic patient records, in addition to the patient administration service. Notes were individually reviewed to ensure that the return was for the same presenting reason as per the virtual fracture clinic attendance.

Patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was measured via telephone interview and a short-form questionnaire. The structure and style of the interview was similar to that of Thelwall (2021). Historically, replies to postal and email questionnaires have been very poor, with Thomas-Jones et al (2022) only receiving a response rate of 45% (45 of 100 patients) despite both telephone and postal contact. As part of its inception, a telephone satisfaction survey was used to collect responses. The authors took a group of 100 consecutive patients and attempted to contact each of them three times. On the initial audit, the authors managed a conversion rate of 76%. The authors duplicated the same number of responses in a more recent follow up for data comparison and review of any trends.

Data analysis

Data were collected and analysed in Microsoft Excel. Quantitative data were tabulated and reported using description statistics. Patient satisfaction data was tabulated and calculated in Microsoft Excel.

Results

A total of 34 979 participates met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study.

Discharge rates

The average discharge rates between November 2014 and November 2022 are reported in Table 1. The mean discharge rate across 2014–2021 was 28% (SD=4). The largest discharge rate were seen in 2014 (43%), with the lowest discharge rate in 2021 (28%).

| Year | Patients attended | Discharged | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 5024 | 2186 | 43 (included ‘the 6’) |

| 2015 | 5217 | 1680 | 32 |

| 2016 | 5363 | 1578 | 32 |

| 2017 | 4887 | 1504 | 30 |

| 2018 | 4583 | 1205 | 26 |

| 2019 | 2837 | 879 | 31 |

| 2020 | 3498 | 951 | 27 |

| 2021 | 3570 | 752 | 21 |

| Total | 34 979 | 10 735 | 28 |

Re-attendance rates

Reattendance rates to the trusts emergency department for the same presenting complaint are shown in Table 2.

| Variable | 2014–2016 | 2019–2021 |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Total patients discharged from virtual fracture clinic | 3866 (38) | 1974 (29) |

| Total returns to the ED within 8 weeks | 319 (8) | 90 (4.6) |

| Total returns with the same issue to the emergency department | 82 (2) | 17 (0.9) |

Patient satisfaction

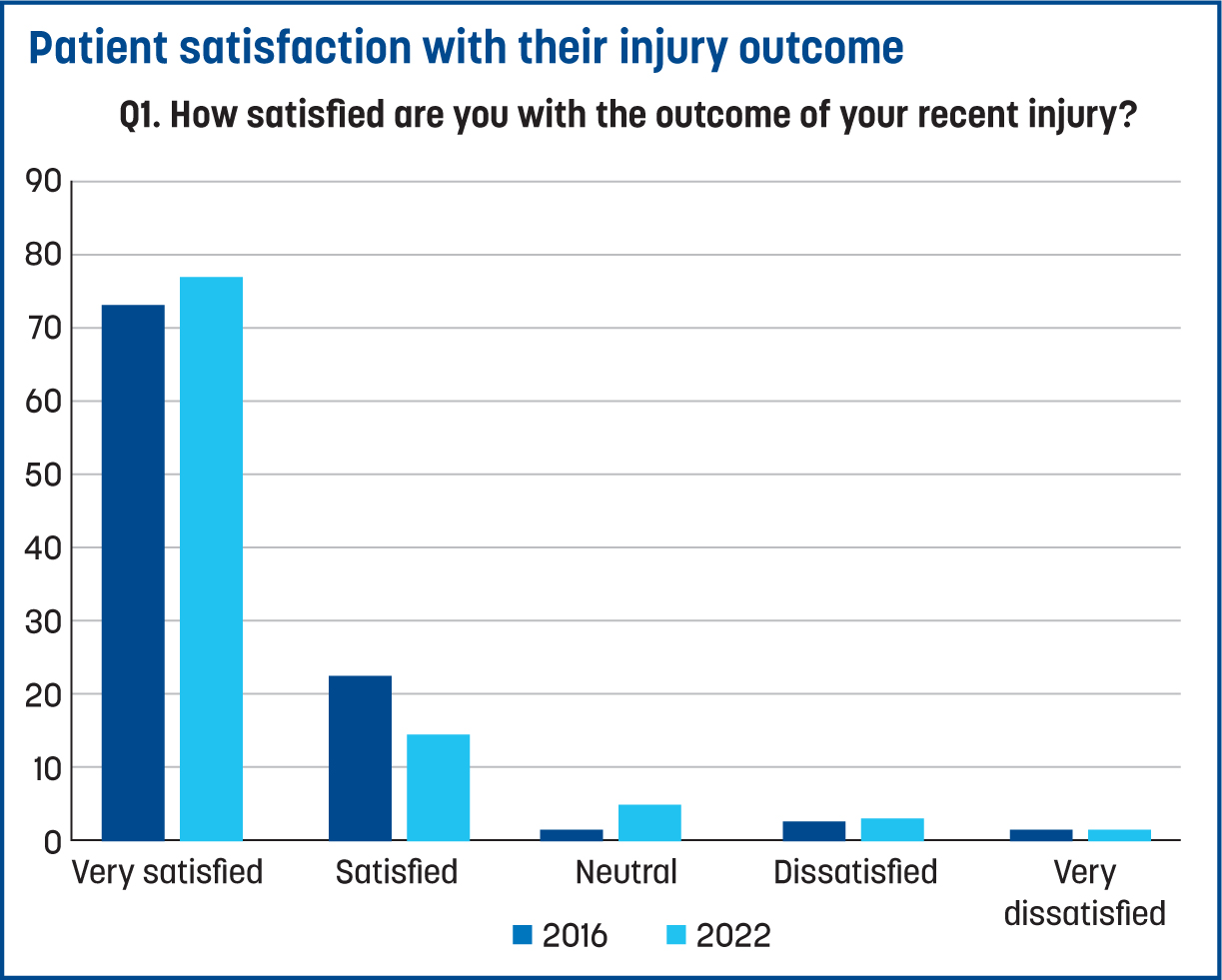

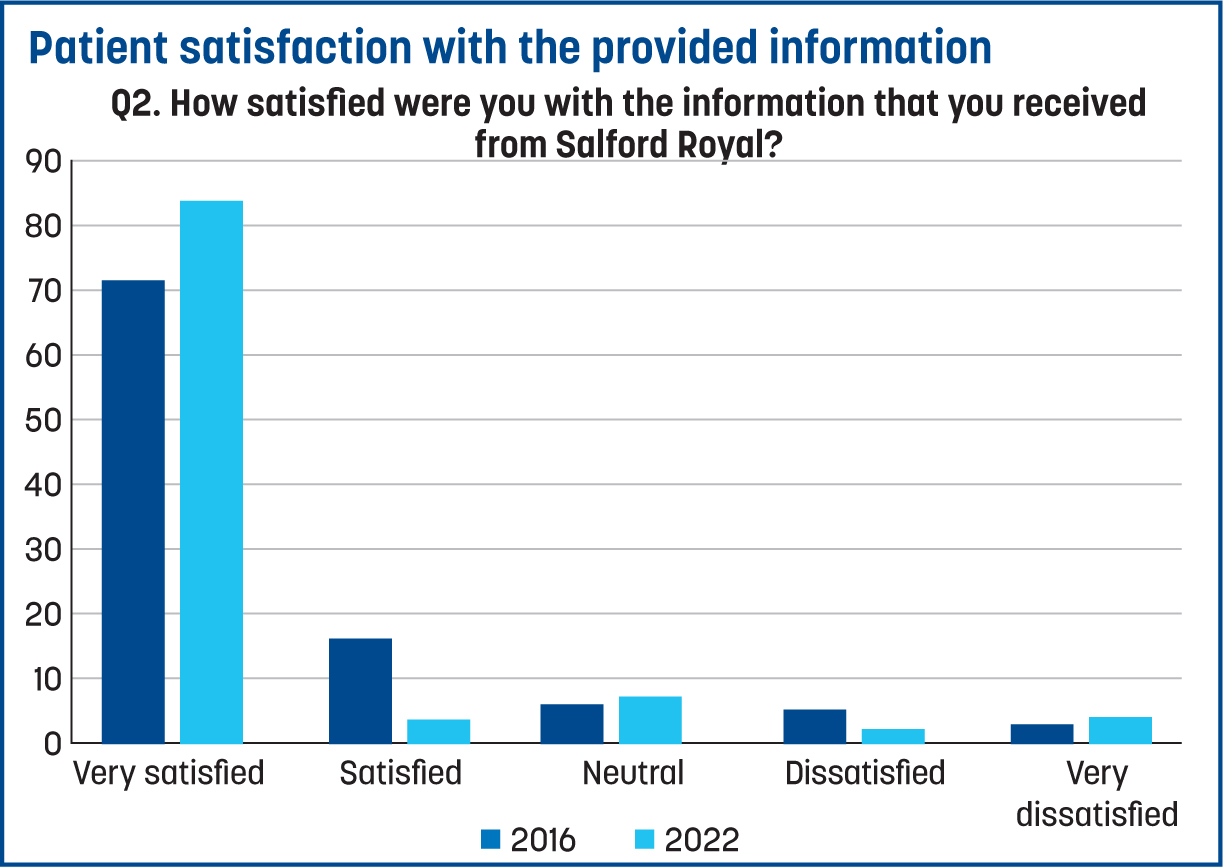

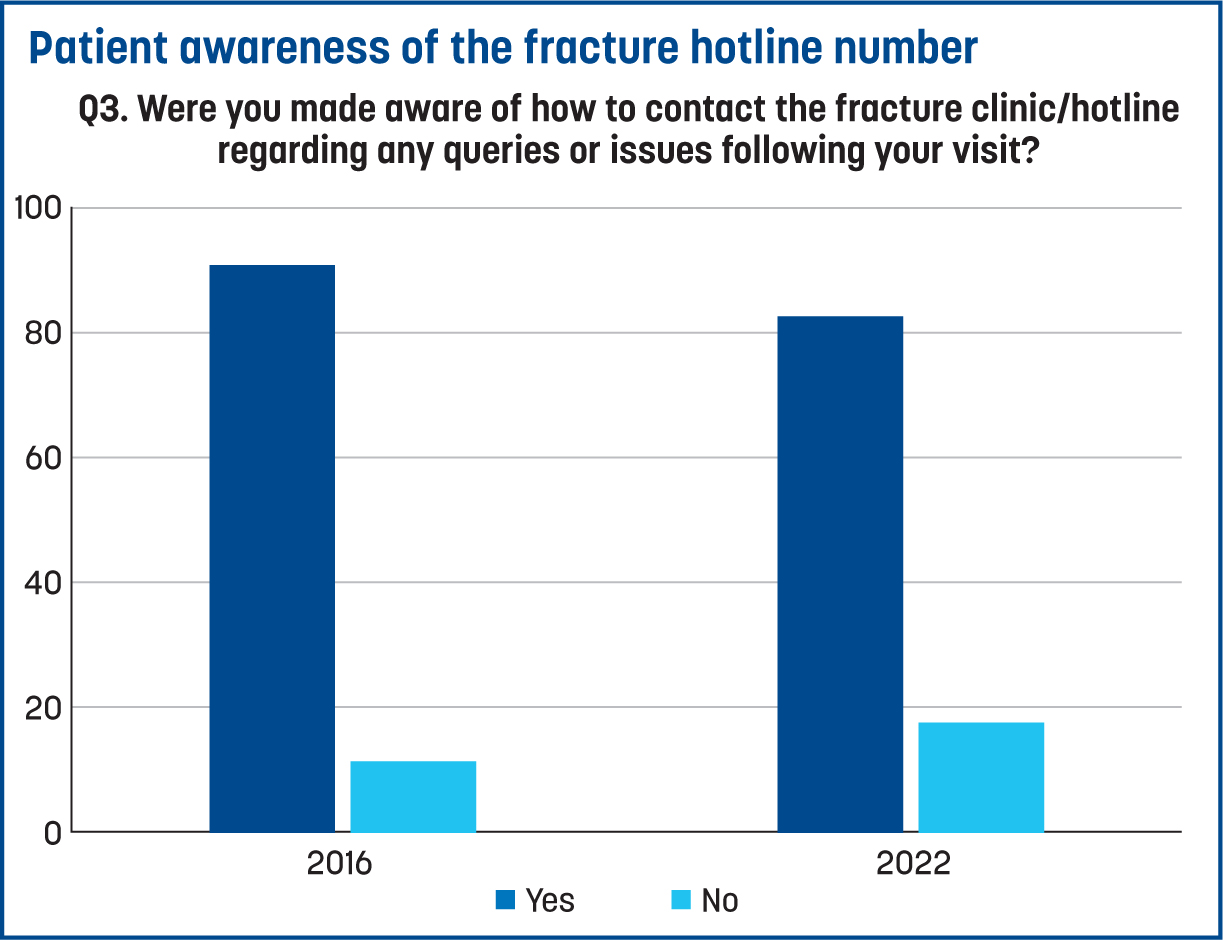

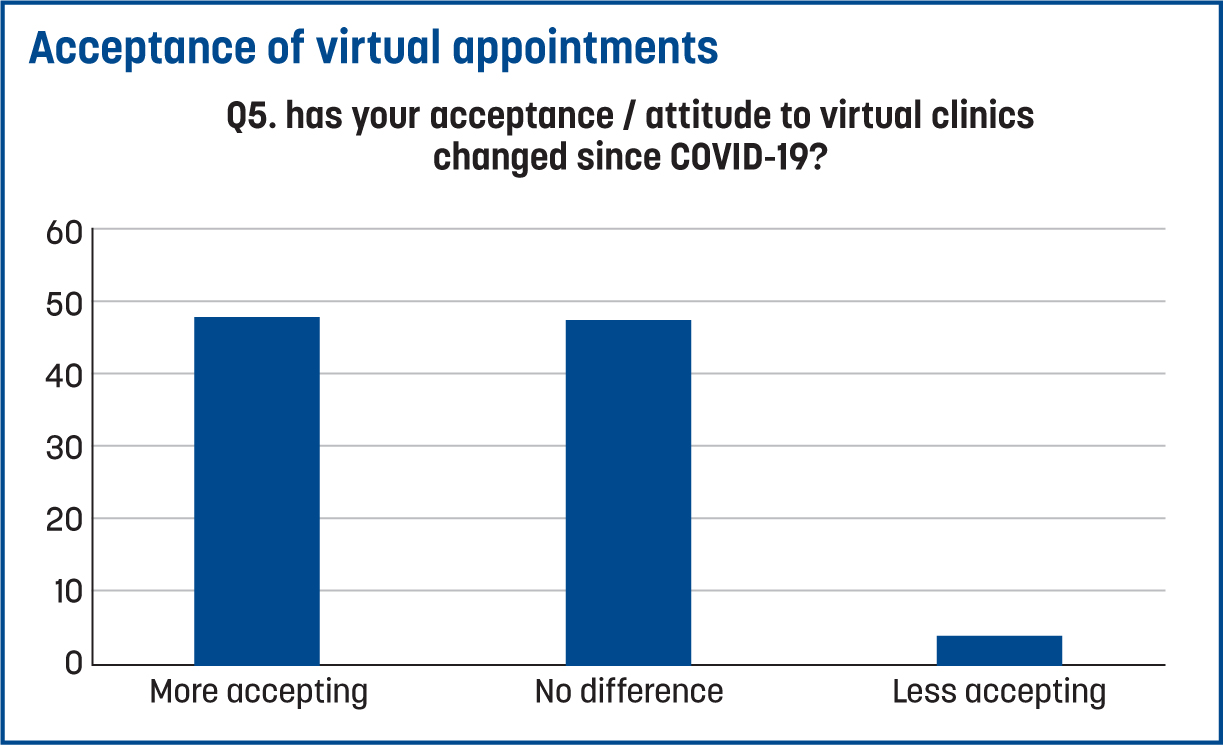

Figure 2 shows that over 90% of patients reported to be satisfied or greater with the outcome of their injury at both time points. Figure 3 demonstrates that 87% of patients were satisfied or greater with the information they were provided regarding their injury at both time points. Figure 4 demonstrates that over 80% of patients were aware they could contact the department hotline for advice. Overall, over 84% of patients were satisfied or greater with their experience, with a trend emerging towards very satisfied on repeat sampling. Figure 5 shows that 48% of patients were more accepting of virtual appointments, with only 4% of patients reporting to be less accepting.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the longitudinal impact of a VFC over an 8-year period. The study focuses on the governance around VFCs, along with the impact on the service and patients. Outcomes are favourable in all domains and complement previous work done over shorter time periods (Thelwall, 2021).

Discharge rates

The discharge rates from the VFC were, when averaged over the 8 years, 28%; this saved 10 735 face-to-face appointments at the fracture clinic. This is a conservative saving of £490 000 over the 8 years studied from fracture clinic attendances alone. Factoring in repeat appointments, imaging and previously proven heterogeneity of fracture management (Kodomuri et al, 2021), the saving would be approximately £1 million. In a time of budget cuts and need for financial scrutiny, the VFC continues to deliver value for money. It is difficult to compare financial savings across the existing literature due to differing methodologies and sources used (Murphy et al, 2020).

In the last year studied, there is a significant drop in the discharge rate, to 21%. The reasons for this are the subject of current further research. Initial discharge rates in the Glasgow model were 39%; these were replicated in the 2014 findings from this study. Like Vardy et al (2014), the initial discharge rate from the VFC identified in this study included many pathologies that are now safely discharged directly from the ED, including the six pathologies from the Glasgow model. This has a direct effect on the rate from VFC, as these pathologies are rarely referred in within current practice. Further cross-departmental working of the trust APP team, alongside consultant orthopaedic colleagues, has led to the expansion of these injuries to include up to 25 different pathologies that can be safely discharged from the ED by a competent practitioner further. This further reduces the discharge rate, as these patients are no longer set to be referred.

Return rates

Recent studies that have also examined VFCs have reported return rates for patients reviewed of 7.5% (Dey et al, 2023), 5.2% and 6.5%, at differing timelines (Cavka et al, 2021). The 2016 return rate at the VFC observed in this study was 2%, followed by 0.9% after repeat sampling in 2021, which is considerably lower. The reasons for this may be multifactorial, but the authors postulate that the use of APPs is linked with a significant reduction in returns to the ED. This could be due to the thorough nature of the rehabilitation information that a physiotherapist can offer versus other models that do not include a rehabilitation specialist. Other studies (Thelwall, 2021; William et al, 2024) show significantly higher return rates, and these are often led by a clinician without the expert rehab knowledge or utilise a system of letter only for discharge. This disconnect between recovery time and information given may be the cause for higher return rates, although further research is needed in this area to confirm this.

The use of APPs has further advantages in that staff can cross-work between both the ED and orthopaedics, via the fracture clinic and VFC. The APPs have direct supervisory responsibility for training emergency nurse practitioner colleagues and provide regular feedback and training via audit and teaching. Further developments within the department have been the establishment of an APP clinic for potential fractured scaphoids (Kodomuri et al, 2021). There has also been the development of two APP-led generic fracture clinics to improve capacity and demand. At the time of writing, these APP clinics (combined) offer 6.6% of the fracture clinic capacity at a major trauma hospital and are the second largest provider by consultant name. They are utilised at over 90% capacity and their performance will be the subject of further research in time.

Patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction with VFCs remains high, as shown by Thelwall (2021), where over 80% of patients were satisfied with the service they received. The results of this study showed that 91% of patient participants were satisfied with their recovery, 87% reported to remain satisfied with the information provided and 85% reported that they felt satisfied or better with the overall service. This is higher than prior studies and, coupled with high levels of awareness of how to contact the department if in need (>80%), may again help to explain the lower return rates. As part of the APP service and VFC, there is a patient hotline for the patients to speak to an APP on a same-day basis with any questions. Our local audit has shown an average of 2 calls per working day to this hotline. These anecdotally are simple queries about progress and the injury, and will help reduce unnecessary returns to the hospital. Patients have reported this service as an example of good practice. These calls are picked up by the APPs performing the VFC, and are appropriately job planned so not to be a clinical burden and form part of the agreed VFC service. There has been a general trend towards more virtual care in healthcare post pandemic, and the data presented in this study would support that this is acceptable to most patients, with 48% of respondents now stating they are more accepting of virtual appointments.

Limitations

This study has a few limitations, specifically:

This study relied on retrospective data analysis within one NHS MTC, which is prone to potential bias. Future prospective studies comparing rates across wider systems are planned and necessary, including financial comparisons of such models. There is also a lack of research on the optimum staffing model for VFCs, mode of discharge and cost effectiveness (Williams et al, 2024). Further research is already underway into staffing models and qualitative factors that may influence the performance of a VFC.

Conclusion

The VFC explored this this study has been safe and effective throughout its duration. It ran for the longest period of time, out of the literature explored. There is a general trend in improving patient satisfaction, with a downward trend in unwanted reattendances. The data appears to be both among the highest for patient satisfaction and the lowest for reattendances. The authors believe this review highlights the quality component of a VFC by having highly skilled advanced physiotherapy practitioners as an integral component.

While the utilisation of VFCs is growing, it is still not in every hospital in the NHS, which shows greater capacity for national savings at scale. VFCs seem less adopted in other healthcare economies. The potential for savings and using technology to access specialist opinions early in rural communities is a potential area for further research.