As global demand for emergency and urgent care continues to grow and staff shortages persist, there is a rising need for innovative and creative health service solutions (Baier et al, 2019). Working autonomously across the four pillars of the multi-professional framework for advanced clinical practice (Health Education England, 2017), advanced clinical practitioners (ACPs) are highly skilled in complex care provision and have the necessary clinical skills, knowledge and behaviours to improve capability and capacity across provider services. Furthermore, the ACP's leadership role provides the opportunity to drive forward continuous service improvement (SI) and minimise waste (Alderwick et al, 2016; Ham et al, 2017; Jones et al, 2022). However, given the profession's relative infancy, measuring the impact on stakeholders and local communities is a critical component. This service improvement project aimed to understand the ACP's role in securing high-quality care provision.

Background

To satisfy the increased need for urgent and emergency care internationally, many health service providers are engaged in widespread reform of their care systems (Baier et al, 2019). In the UK, the same-day emergency care (SDEC) model builds upon the previous work of ambulatory care services and is designed to provide a comprehensive model of care by ensuring patients receive the right care, in the right place, and at the right time (NHS England, 2013; NHS Improvement, 2018). By offering a consistent approach to specialist care delivery, they can also reduce unnecessary admission to hospitals and limit the occupancy pressures faced by acute trusts (NHS England, 2020). However, as a result of the wide variety of referral pathways and clinical presentations, patient selection, streaming and triage can be extremely challenging, adversely impacting early evaluation and treatment, which are critical factors for clinical stability in acute illness (NHS England, 2019).

Adhering to the Standards for Ambulatory Emergency Care (Royal College of Physicians and Society of Acute Medicine, 2019), SDEC performance metrics include the completion of clinical observations contributing to the NEWS2 score within 30 minutes of arrival, clinician review within 1 hour and the use of validated risk stratification tools to guide care management, including the need for further investigation. However, nationally, a lack of available data on compliance with key metrics and more general data in relation to the success of SI initiatives is evident, limiting opportunities for shared learning across the sector. In response, the main aims of this article were:

Methods

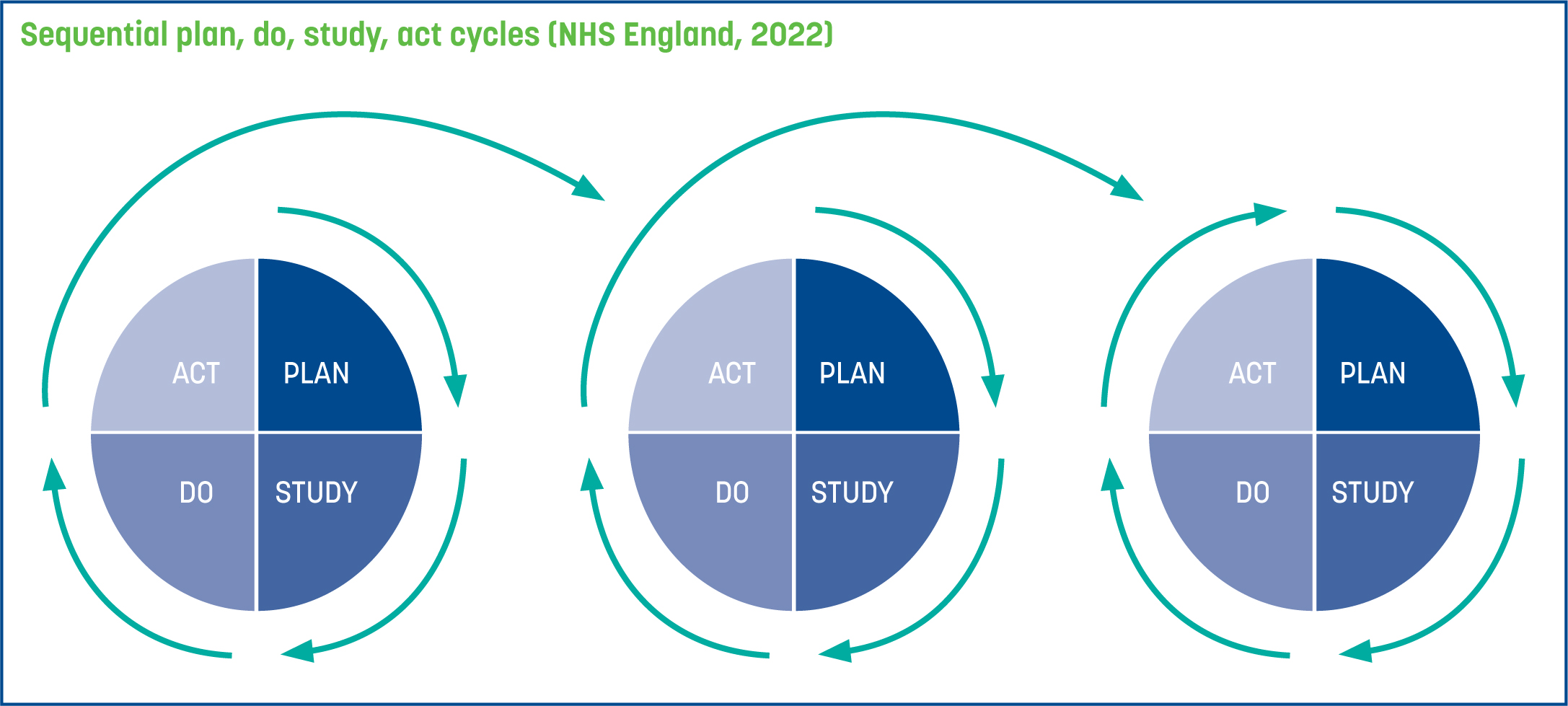

The SI project adopted a sequential Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) improvement model (Figure 1) as the overarching methodological framework (NHS England, 2022). This decision based on the scientific merit of the model and its capacity to iteratively test changes before wholesale implementation (Taylor et al, 2014).

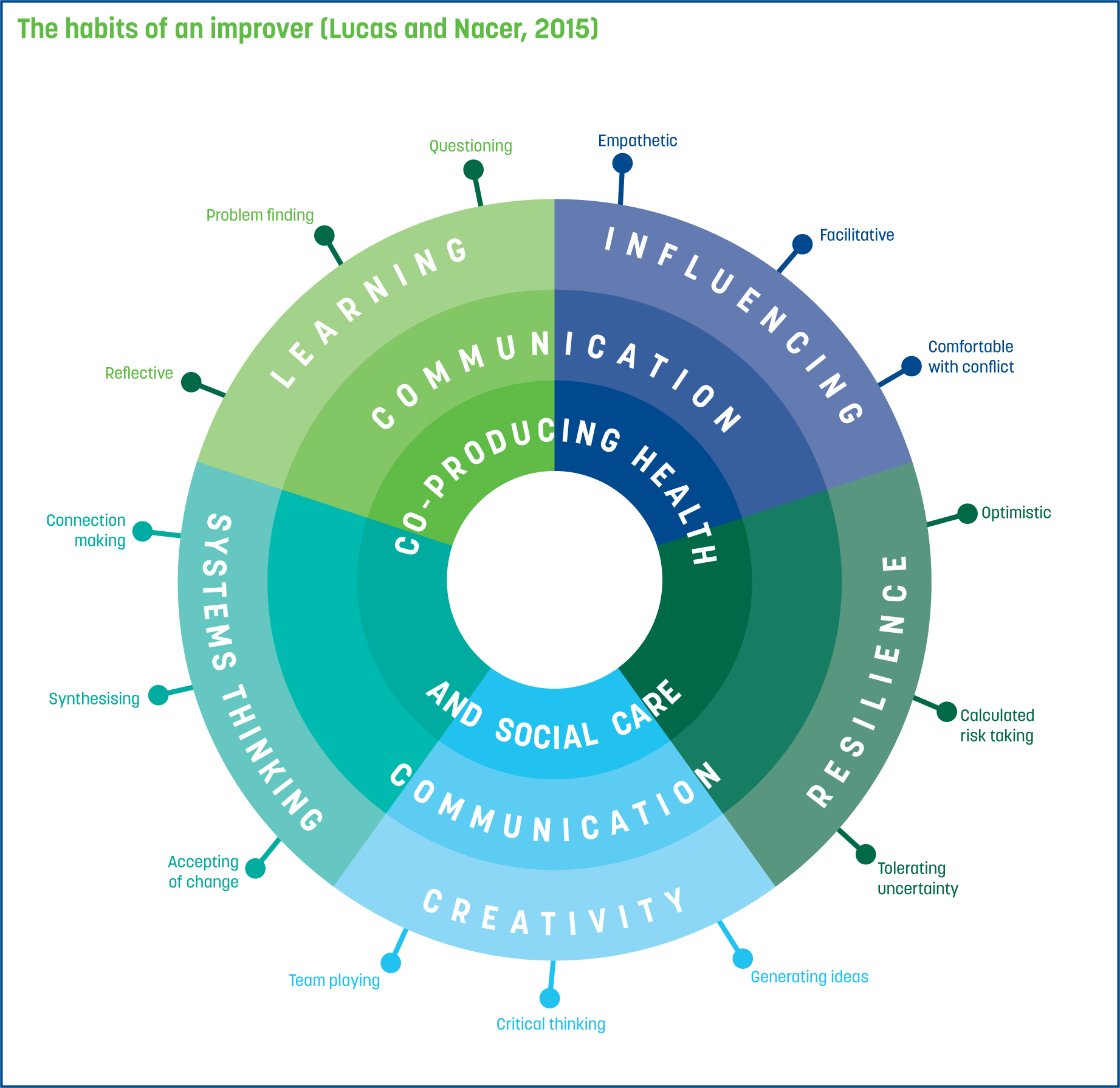

The PDSA methodology was further augmented by process mapping of the patient journey through SDEC and coalition formation with key stakeholders. Lucas and Nacer's (2015) habits of an improver provided a useful analytical framework to stimulate group collaboration, develop capability and cultivate individual abilities (Figure 2).

Audit data analytics were used to quantify the impact of the interventions during each sequential PDSA cycle, and the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (2020) best practice in clinical audit standards ensured rigorous governance mechanisms were in place to monitor impact against set values. This included data relating to the total number of patients presenting each day across a 7-day period; the percentage of patients receiving a NEWS2 score within 30 minutes (target 90%); and the median wait time for clinician evaluation (target 1 hour). The trust audit team performed confirmatory data analysis of each data set, prior to evaluation by the first author who has a background in SDEC provision and the second author, who is an experienced researcher. The iterative exploratory and confirmatory processes were used to inform subsequent SI activities.

Ethical approval

Full ethical approval was obtained from an ethics committee at a local higher education institution as part of an accredited ACP programme of study, in line with institutional guidelines. In accordance with relevant data protection legislation, the SI project and clinical audit were both registered with a local trust audit department, and Caldicott approval was obtained (Department of Health, 2016). All collected data were stored and protected in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulations (Data Protection Act, 2018).

Results

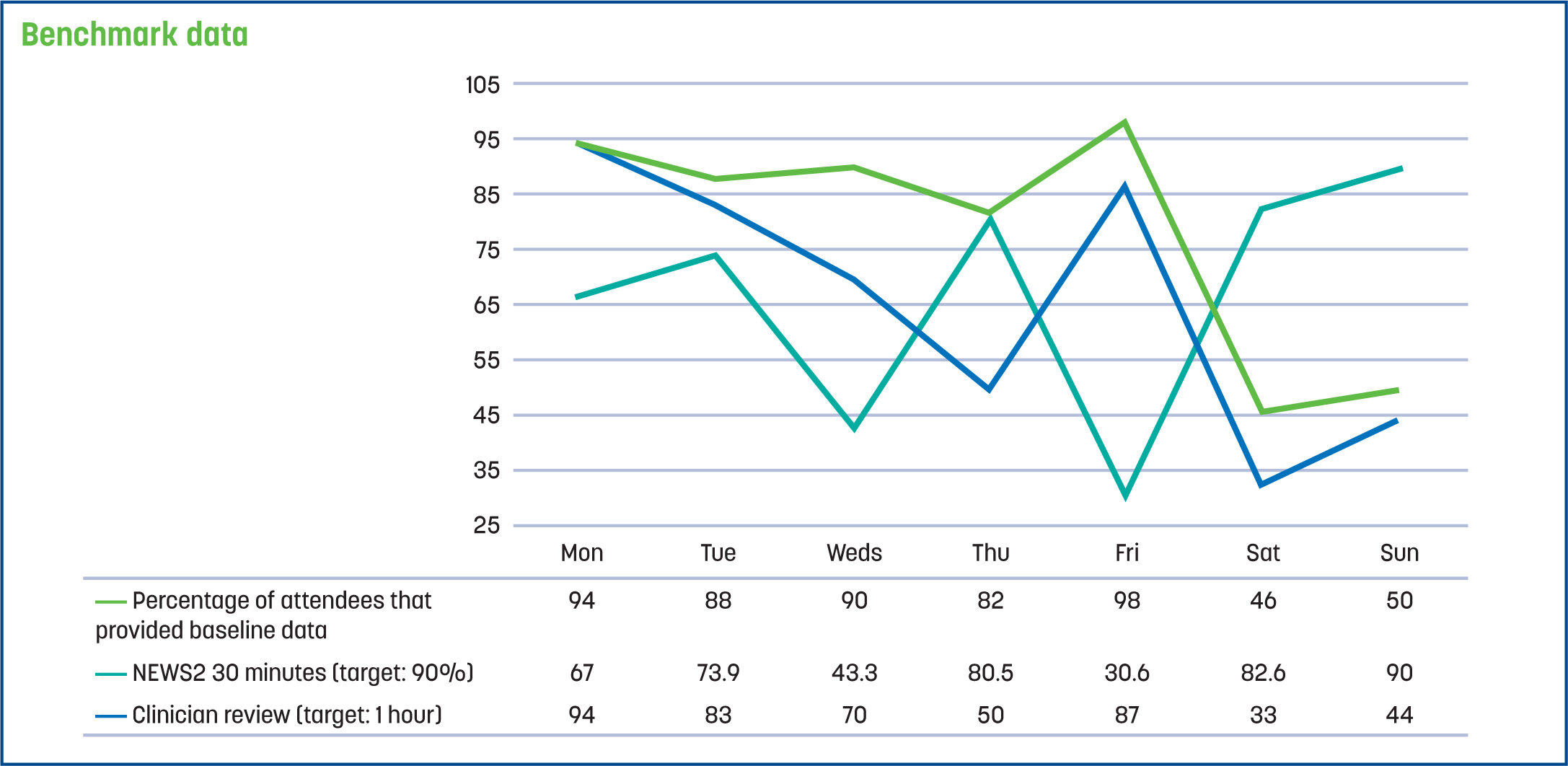

The baseline audit data analytics showed that 548 patients attended the SDEC unit in a 7-day period. There was a mean number of 90 patients on Monday to Friday and 48 patients on Saturday to Sunday, over the course of 14-hour daily opening times. The target percentage of patients receiving a NEWS2 score within 30 minutes (90%) was not reached on 6 out of 7 days, with a median value of 70.45% (longest wait time: 3 hours and 24 minutes). Breaches for clinician review (target 1 hour) occurred on 4 out of 7 days, with a median wait time of 1 hour 29 minutes (longest wait time: 4 hours and 50 minutes) (Figure 3). The time taken for NEWS2 and clinician review were shorter on a weekend when fewer patients attended the service.

Process mapping of the patient journey through the SDEC unit with stakeholder coalition identified several issues with process, impact and balancing measures. Process measures included the array of referral protocols and the number of patients requiring examination on the unit, the volume of patients causing a bottleneck in triage and increased overall length of stay. Impact measures were linked to the effectiveness of the triage system and the inability to effectively identify and request diagnostic tests at the earliest opportunity, a difficulty exacerbated by a lack of knowledge and skills identified in relation to key conditions, including the investigations required for specific medical presentations. Balancing measures included the volume of unplanned attendees and re-attendees requiring follow-up care, the available skill mix in terms of adequate patient-to-staff ratios, and the subsequent availability of onward care pathways.

To address the highlighted difficulties, a Collect-Analyse-Review (CAR) cycle was adopted and a series of process improvements were made to the unit's operation. This included changes to the skill mix and the relocation of one healthcare assistant (HCA) to complete the NEWS2 score and one nurse practitioner (NP) to triage to speed up early assessment and treatment plans.

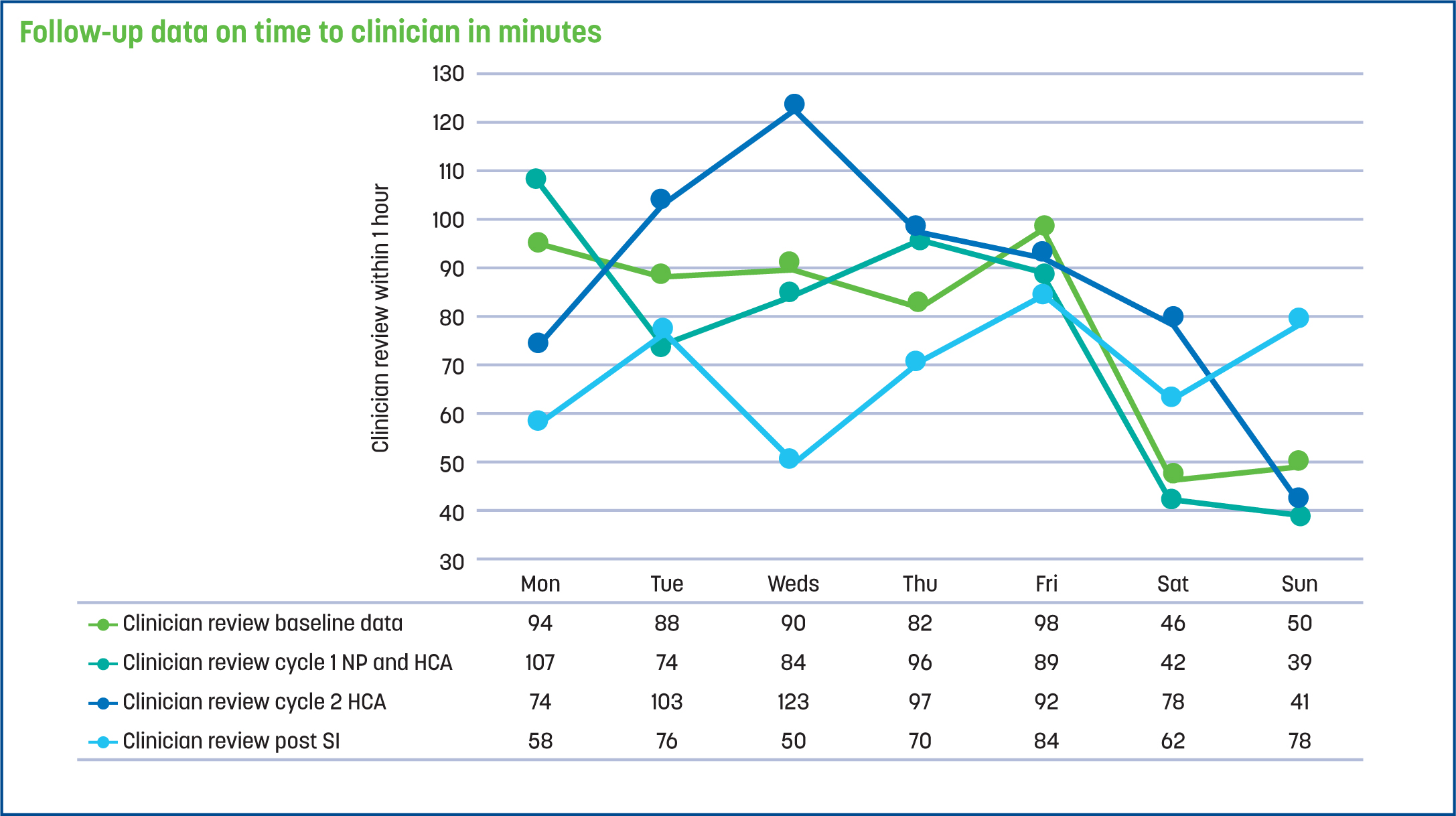

The follow-up audit indicated that in the subsequent 7-day period, the percentage of patients receiving a NEWS2 score within 30 minutes (target 90%) rose 4.30% and the maximum wait time fell from 3 hours and 24 minutes to 1 hour and 31 minutes, indicating some positive effects of the additional HCA (n=549). However, breaches for clinician evaluation (target 1 hour), rose to 5 out of 7 days (with the maximum wait time rising to 6 hours and 9 minutes), and the overall median wait time only fell by 2.5 minutes to 1 hour and 27 minutes, mitigating any benefit of the NP move to triage.

Following a full impact analysis, a series of educational sessions were held with all grades of staff regarding common presenting conditions and clinical investigations. The NP was also moved back to assessment. Overall, evaluation of the impact of the SI initiatives following the second PDSA cycle revealed a subsequent fall of 4.95% in overall compliance with NEWS2, lowering to 69.80%, and a continued lack of compliance with clinical review, with overall clinician review time rising by 7 minutes to 1 hour and 34 minutes.

Given the continued variability and lack of statistical significance, an additional mapping exercise was undertaken over a 28-day period to map the staff-to-patient ratio and explore the impact that staffing levels had on the NEWS2 score and clinician review. Findings indicated that staffing levels were inadequate to meet the volume of patients attending, especially on weekdays with a higher number of attendees (the staffing ratio required 5.2 patients per staff member to achieve compliance). In response, higher-level intervention was required, and a business case was presented to the trust board for the recruitment of two extra nurses and two extra HCAs to work Monday–Friday from 10am to 6pm (the busiest operating times). The trust board approved the recruitment of two registered nurses, one HCA, and the opening of an additional triage resulting from presentation of sequential cycles and audit data analytics by the ACP; these staffing requests had previously been rejected because of the lack of verifiable data. Following recruitment to the service and changes made to the operating model, follow-up data were collected. The findings indicated that the completion NEWS2 score within 30 minutes (target: 90%) rose by 14.05% to 84.30% from baseline data, although it was still below the target range (Figure 4).

Breaches for clinician review (target: 1 hour) fell from a median wait time of 1 hour and 29 minutes to 1 hour and 13 minutes. This decrease of 16 minutes still left the median wait time above the 1 hour target (Figure 5).

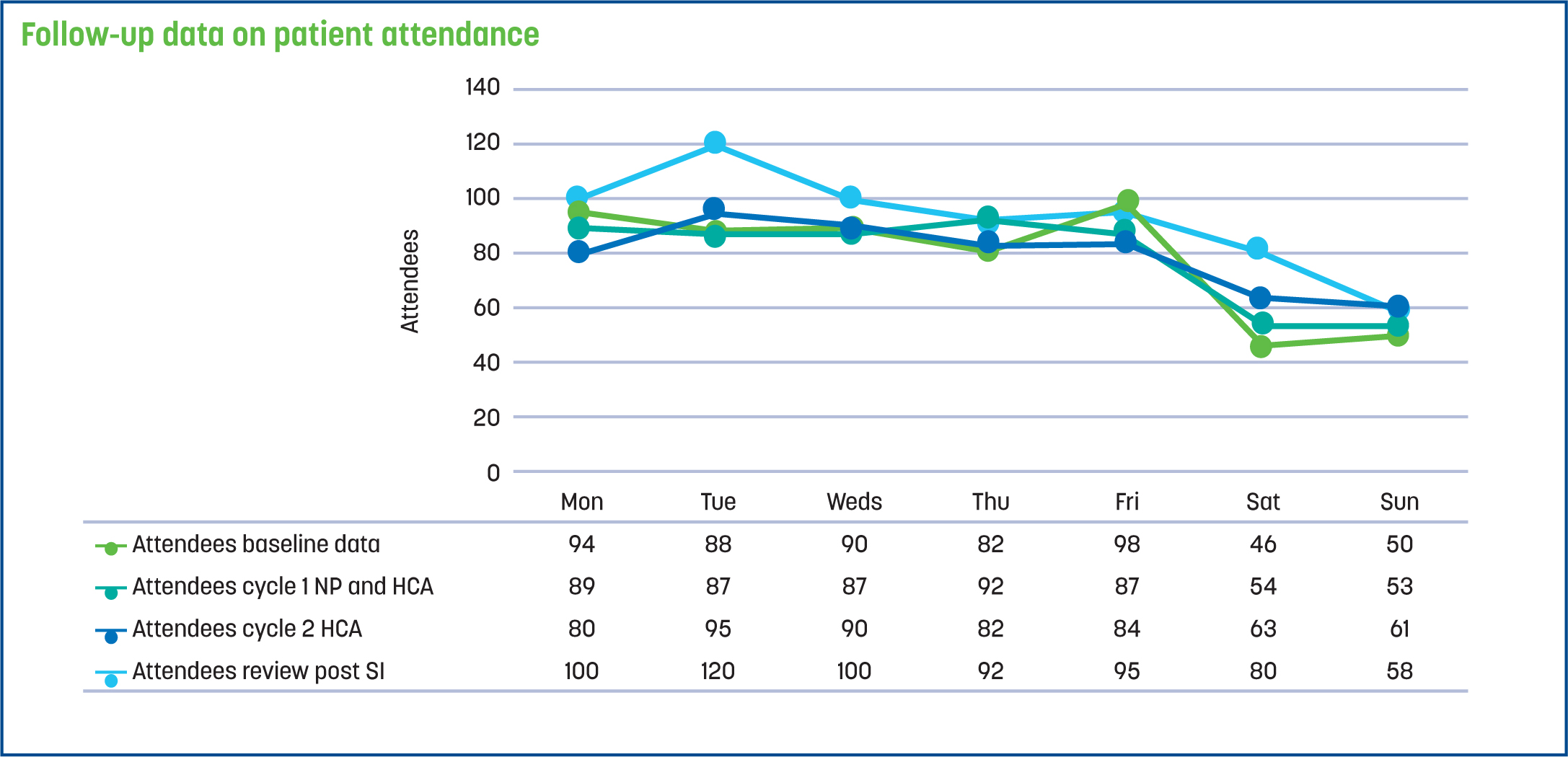

Data on patient attendance were also collected. The findings demonstrated that demand continued to grow; the median number of patients attending each day rose from 90.4 to 101.4 (11.0% increase) on a weekday and 48.0 to 69.0 (30.5% increase) on a weekend. This is an outcome mitigating the full benefit of additional staffing, both during the week and on a weekend when fewer staff are rostered, and alternative treatment and diagnostic pathways may be limited (Figure 6).

Discussion

This SI project set out to measure compliance with the standards set for ambulatory emergency care, reduce variability, and improve care provision at a regional SDEC in the UK (RCP and SAM, 2019). The findings highlight the importance of adopting a systematic approach to SI, regardless of the area of practice and the need to carefully evaluate the impact of confounding variables. This includes the diversity of referral routes, the severity of illness and underlying conditions, all of which are complex factors that make the causality of SI initiatives difficult to evaluate. In the UK, it is anticipated that with the introduction of the delivery plan for recovering urgent and emergency care services, demand for SDEC and complexity will continue to grow (NHS England, 2023a). In response, strategies to process map referral routes and pathways of care will be of vital importance to try and ensure a streamlined service.

The impact of factors relating to staff expertise, levels of education and clinical competency are also difficult to measure, given the relative infancy of SDEC units. This issue is recognised in NHS England's (2023b) recent publication, the same day emergency care: competency framework, which is designed to ensure a skilled, confident workforce. Regardless of their place of work, in their capacity as clinical leaders and educators, ACPs need to continually reflect on their role in enabling staff to demonstrate competency as expert-level practitioners. This is important as services continue to grow and adapt to change.

The SI project also identified that outcome measures will fail without an adequate workforce to support the changes made. The NHS Long Term Workforce Plan (NHS England, 2023c) brings this position into clear focus and highlights the enduring issues of recruitment, retention and training affecting healthcare. In response, requests for additional resourcing must be underpinned by robust evidence if they are to gain funding, and the ACP needs to co-opt the support of staff with the technical and digital capabilities to help produce rigorous data (Health and Social Care Committee, 2023). Digital expertise and literacy skills are being used to benchmark the impact of the changes made and their contribution to patient care and quality, helping to sustain services and retain staff.

It is evident from the wider national and international literature that the need for improvement-led delivery in urgent and emergency care has gained significant traction (Baier et al, 2019; NHS England, 2023a). In response, healthcare providers, including ACPs, will be expected to work in partnership with care boards, connecting previously disparate systems and supporting staff to share ideas using one high-level approach. To achieve this ambition in the UK, the first National Improvement Board chair and deputy chair have just been appointed, and national priorities are due to be released in the coming months. A national leadership for improvement programme is also due to be launched, offering a consistent approach to board-level training. Moving forwards, ACPs will need to stay abreast of the developments and seek out opportunities to demonstrate their impact and contribution given their relational authority based on trust and mutual respect.

Conclusions

Engaging in SI is a difficult task, and in response, the ACP needs to adopt a whole-system approach, eliciting buy-in and support at all levels of the organisation to fully maximise its impact and spread. Maintaining a firm commitment to the systematic assessment and evaluation of each cycle of improvement, including demand and capacity measures, can lead to demonstrable improvements in the quality of care for patients and staff experience. As the demand for healthcare rises and staff struggle with limited resources, ACPs as clinical leaders are at the forefront of change sharing learning and good practice in relation to improvement-led delivery.