According to the United Nations' Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2022), 10% of the world's population and 19% of Europe's population is aged 65 years or over. Chavez et al (2017) report that by 2045, the number of people aged over 80 years will have increased threefold. Advancing age manifests physiological and psychological changes that can eventually cause an overall decline in a person's health or everyday function. This functional decline is defined as frailty, or frailty syndrome (Wyrkro, 2015). According to Dolenc and Rotar-Pavlic (2019), ageing and frailty create an increased risk of hospitalisation, premature death and disability, as well as reduce the individual's overall quality of life (QOL). It also has increased the demand for 24-hour residential/nursing home care admission.

Currently within the UK, 340 000 people live in a care home, with one in seven residents aged 85 years or above (Waldron, 2021). Craig (2021) reports a significant 30% increase in care-home placements within the last 4 years. Additionally, 75–85% of care-home residents have high levels of disabling complex conditions that require regular review and intervention, which also increases the risk of exacerbation and hospitalisation. Wolters et al (2019) found that 7.9% of hospital admissions in 2016–2017 were care-home residents; however, 41% of these cases were evaluated as unnecessary, being deemed as manageable within the community. Barker et al (2018) add that due to their complex needs, elderly care-home residents have increased rates of in-hospital death, inappropriate prescribing and poor chronic disease management. In response to such findings, there has been an increased drive to reform healthcare and delivery tactics in the UK, in order to meet the expected increase in demand.

Supporting people to ‘age well’ is an ambition of the NHS Long-Term Plan (NHS England, 2019). The White Paper sets out to improve care delivery in primary care and community services, and reduce the growing demand within secondary care (Alderwick et al, 2017). The framework for enhanced healthcare in care homes (EHCH) (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2020) was borne out of the long-term plan, and provides an effective agenda of healthcare reform within care-home communities, as well as clear goals and timeframes to achieve them. It identifies key elements of care to be regularly reviewed, including medication, nutrition, oral hygiene, continence, falls and dementia. It also recommends primary care practitioners with advanced clinical decision-making skills having access to ‘home rounds’, rather than leaving the responsibility solely to GPs.

The role of the advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) has evolved over the last 20 years, developing in part to meet the shortfall of GPs and geriatric specialist doctors. Initially, the role was pioneered in the US and Canada, to bridge the staffing gap of medical physicians. The ANP role now exists in 27 European countries, Australia and New Zealand, with practitioners having varying levels of exposure, experience, competence and training (Chavez et al, 2017).

ANPs have been in the UK for around 30 years, and have been the subject of much debate and discussion (Boyd et al, 2019). Despite there being significant evidence of ANP-related clinical benefits across the US and Canada (Donald et al 2013), there is a lack of UK studies involving ANP healthcare service models in care homes (Burns and Nair, 2014).

The introduction of the ANP role within care homes has been recommended in the UK since 2005; however, prior evaluation of the potential benefits published nationally to date appear anecdotal and in isolation (Craig, 2021). Despite the abundance of government agendas calling for national and local improvements to healthcare access and outcomes for elderly residents within care-homes, there still lacks an ideal ANP-specific care model.

Aims

This paper was designed to establish a robust understanding of the community ANPs' impact on care home residents' health, to drive future evidence-based practice service-delivery. It aimed to identify, synthesise and critically review the available primary research, and establish the evidence around ANPs involvement in the health-outcomes of elderly, frail residents living in care-home facilities. It also aimed to present a thematic analysis of how the ANP enhances healthcare outcomes.

Method

Design

This study was designed in relation to an evidence-based medicine hierarchy pyramid (Rosenfield, 2017). At the top of the pyramid are meta-analyses and systematic review (SR) papers that collate primary research and compare results. Cardoso et al (2019) agrees that SR is the highest level of evidence to guide constructive evidenced-based practise, adding that nursing has become multi-dimensional, involving socioeconomic, political and cultural drivers that require a rigorous approach when gathering thorough evidence.

As a result, this paper will incorporate a critical review of the literature available, as well as adopt a systematic literature search approach. Combining a critical synthesis of primary research papers, with a systematic and comprehensive search of the literature, will ensure that evidence can be appraised in a structured way (Polit and Beck, 2018).

Sources of data and information

The primary sources of information for this review were gathered from CINAHL, MEDLINE and EMBASE via Athens account and the university and NHS trust library, following guidance from librarians.

To facilitate the development of search term criteria, the Patient, Exposure and Outcome (PEO) framework (Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry, 2013) was adopted (Table 1). Papers that were included were peer-reviewed primary research papers that had been published in English language over the last 20 years (Table 2).

| Population | Exposure | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Care home | Advanced nurse practitioner | Healthcare |

| Elderly | ||

| Frail | ||

| Aged care | ||

| OR | AND | AND |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Primary research papers | Un-peer reviewed papers |

| Peer reviewed | Unpublished thesis papers |

| English language only | That involve other advanced clinical backgrounds other than nursing |

| Within the last 20 years | Systematic reviews |

| Involving advanced nursing roles working within long term care homes. | Non-English speaking |

| Patient care aged over the age of 65 years or frail | Aged over 20 years old |

Systematic literature review approach

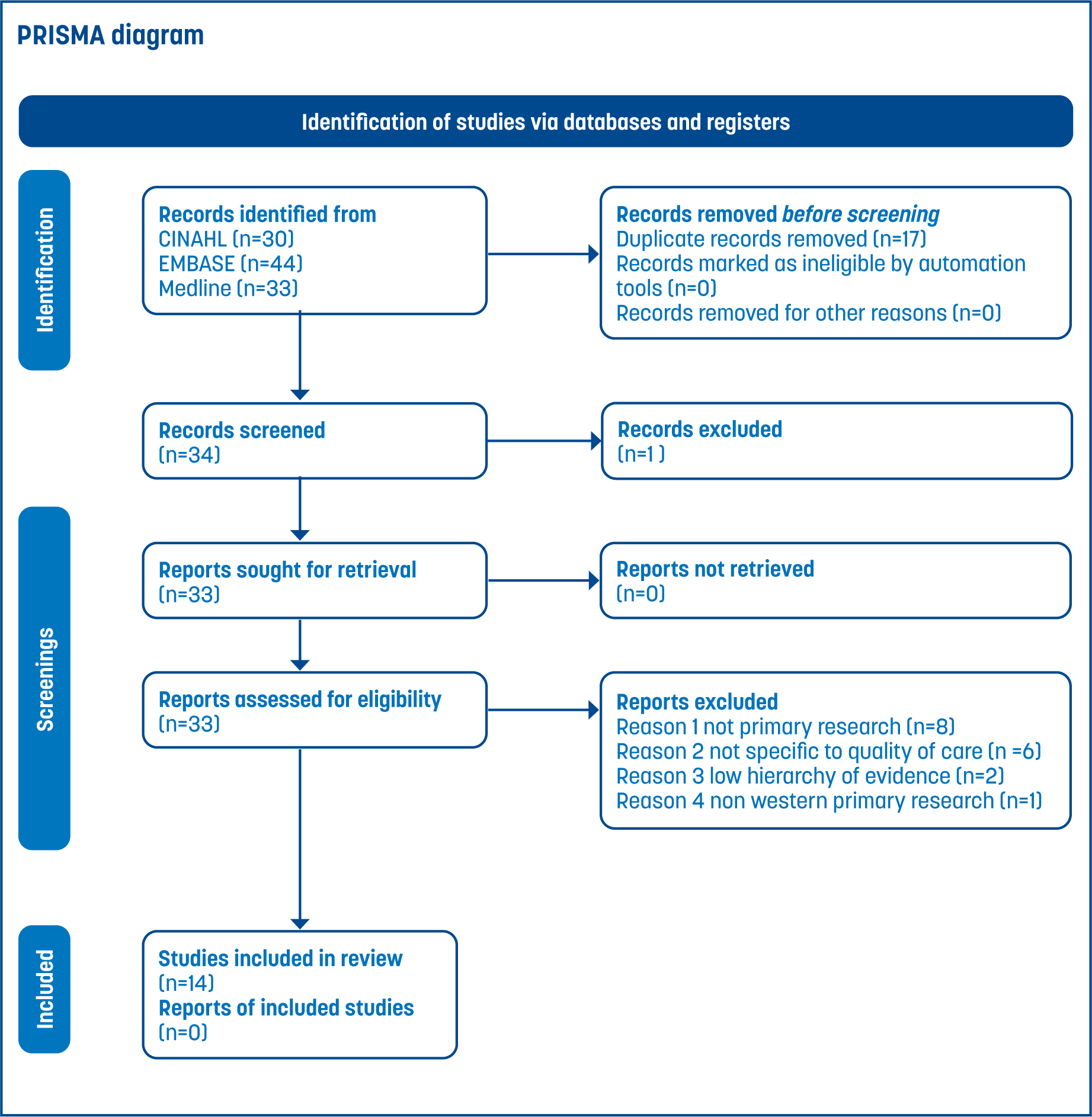

The adoption of the PRISMA flow chart was utilised for the purposes of literature selection (Figure 1). This was to ensure use of a recognised robust system that has been widely accepted, so as to allow for replication of the approach.

Quality review/synthesis of literature

Suitability of individual papers in this critical review was sought by the primary researcher (HR), who evaluated the paper based on the research question and inclusion criteria. Once selected, synthesis of the papers was performed for their quality of the research via ratified appraisal tools. The toolkits adopted to critique the selected papers were that of the Joanne Briggs Institute (JBI) website and the mixed-method appraisal tool (MMAT) by Hong et al (2018)

Data synthesis involved the collation, combination and summary of findings in individual studies included in the review. An initial descriptive synthesis was performed by tabulating the details about the study-type, number of participants, interventions and summary of outcomes-measures. Subsequently, a thematic approach was adopted, followed by a narrative synthesis to fully interpret the collated evidence.

Results

A total of 14 studies met the final inclusion criteria. Four English language countries were represented, including two papers from the US, six from Canada, four from Australia and two from the UK. All papers involved ANPs working within care-home facilities. Of the 14 selected papers, three were experimental by design. Of the three experimental design papers, all were quantitative, involving a prospective randomised controlled trial approach. The remaining 11 were observational.

All observational studies reviewed involved prospective cohorts of care-home facilities with ANPs, or case studies/reports to evaluate the impact that ANPs had on the care-home residents. Two were quantitative, three were qualitative. The remaining six incorporated mixed methods of quantitative and qualitative data.

Discussion

Five outcome themes were recurrent throughout the synthesis of the results. They were, in order of prevalence:

Improved/equivalent quality of care

Eight studies found that ANPs generated an overall improvement in the delivery of care (McAiney et al, 2008; Klassen et al, 2009; Neylon, 2015; Arendts et al 2018; Boyd et al, 2019; Kilpatrick et al, 2019; Campbell et al, 2020; Kilpatrick et al 2020). The improvements consisted of improved rates of medication reconciliation, wound/pressure area care, reduction in falls, increased chronic disease review/management and advanced care planning. This corresponds with the outcomes required to be achieved in the EHCH agenda by 2024 (NHS England, 2020).

ANPs were also shown to improve care staff confidence due to their wider knowledge base, education in healthcare and communication skills. A SR by Barker et al (2018), which looked at who should deliver primary care to residents in long-term care, found that ANPs offered additional supportive and educational skills over and above the GP role.

Dangwa et al (2022) also discussed the benefits of ANPs involvement in long-term care as strong communicators, educators and role-models that demonstrated leadership qualities. A SR by Donald et al (2013), which reviewed four quantitative prospective studies, found that the involvement of ANPs reduced depression, urinary incontinence, pressure ulcers, use of restraints and aggressive behaviour in patients. While this review was one of the first to consider quality-care outcomes from ANP-delivered care, it only reviewed US-based papers. Christian and Baker (2009) conducted a SR exploring the effectiveness of ANPs, however, they only focused on hospital avoidance as an indicator of effective care in the US.

Five other studies (Kane et al, 2004; El-Masri et al, 2015; Dwyer et al, 2017, Craswell et al, 2019; Ryskina et al, 2019) indicated equivalent or non-significant improvements in care-quality in relation to the ANP role. These studies were more clinically robust, hierarchy studies that utilised experimental designs, control-groups and blinded research. They also covered larger and, in some cases, longer timeframes, which further validates their findings. Kilpatrick et al (2020) summarised that quality of care can be defined in several ways; therefore, such studies require clearer definitions in respect of a minimum dataset to provide better objectivity.

Successful collaborative role

This theme, which was discussed in 10 papers, was summarised as improving health-outcomes, using a consultative model involving multi-professionals (Kane et al, 2004; McAiney et al, 2008; Klassen et al, 2009; Neylon, 2015; Cordato et al, 2017; Arendts et al, 2018; Craswell et al, 2019; Kilpatrick et al, 2019; Campbell et al, 2020; Kilpatrick et al, 2020). Wells and Tolhurst (2021) discussed how as care-home residents had greater health demands and often complex co-morbidities, they required care via a holistic, multi-disciplinary approach. Dangwa et al (2022) added that the focus of care home residents should be QOL and safety of care, and the most appropriate member of the healthcare team should be utilised in the provision of such. These findings lend themselves well to the ethos of ACPs MSc-level of training, which straddles across both the medical and nursing models (HEE, 2017). Barker et al (2018) solidified this attitude further through their UK-based SR, which indicated—from the 24 multinational studies explored—that specialist nurses offer supplementary and complimentary care, in addition to the work of physicians.

Reducing potentially avoidable hospital admissions

A total of nine primary research papers (out of a possible 14), demonstrated that ANP-led services led to a reduction in hospitalisations (Kane et al, 2004, McAiney et al, 2008; Klassen et al, 2009; El-Masri et al 2015; Cordato et al, 2017; Dwyer et al 2017; Craswell et al 2019; Kilpatrick et al, 2020; Campbell et al 2020). This suggests that ANPs working within care homes, through successful collaborative working, can reduce unnecessary hospital admissions and keep care closer to home. Similar results were found in Christian and Baker (2009), who selected seven US-based experimental papers, all of which indicated reduced hospitalisation rates when ANPs were part of the multi-disciplinary team. While this was a robust SR, which was found within the JBI library and had no stated conflicts of interest, US-based ANPs typically come from differing educational backgrounds; as such, these findings cannot be generalised across other international zones.

Timely access to primary/secondary care

Out of the selected studies, a total of seven papers (McAiney et al, 2008; El-Masri et al, 2015; Dwyer et al, 2017; Boyd et al, 2019; Craswell et al, 2019; Kilpatrick et al, 2020; Campbell, 2020) discussed how timely access to primary/secondary care, as a result of ANP involvement, increased the provision of quality care.

Patient/family/colleague satisfaction

A total of five papers (McAiney et al, 2008; Klassen et al, 2009; Neylon, 2015; Dwyer et al, 2017; Kilpatrick et al, 2019) found that the presence of ANPs improved the level of satisfaction felt by colleagues, patients and their families. Barkerjian's (2008) study, which demonstrated that the presence of an ANP improved patient/family and staff satisfaction, led to the recommendation that ANPs be employed directly within care homes in US. This measure has also recently been proposed in the UK (Craig, 2021).

Strengths and limitations

This paper provides a range of contemporary evidence as to how the ANP role improves the standard of care provided to frail older patients living in care facilities. Although some of the primary research reviewed were lower down on the hierarchy of evidence when appraised alongside similar robust experimental studies, the gathered sources collectively provide a multi-centric review of the robustness and relevance of the ANP role. The findings of this study are also in line with the findings of several other SRs conducted in the last 15 years. Converse to the SRs reviewed, this paper amalgamates finding across a range of countries, including the US, Canada, Australia and the UK, and utilises a plethora of academic journals that focus on nursing, research, medical and geriatric-based topics.

This study also had several limitations. There was no consistency across the reviewed studies as to what level of skill, knowledge and training ANPs needed to complete their role. Although certain studies did address the necessity of MSc-level of knowledge, the skills and experiences of each ANP employee were not evaluated. There is still great disparity and variability as to what the background and knowledge base for an ANP should be (Mileski et al, 2020).

Another limitation is the lack of UK-based research into the community ANP role. Most of the published research explored in study was conducted in the US, Canada and Australia. This is in part due to the earlier utilisation of the ANP role in care homes (Donald et al, 2013; Chavez et al, 2017). While some US-style programmes have been adopted in the UK, such as the ‘Evercare’ programme being implemented across nine primary care trusts (Jehan and Nelson, 2006), more UK-based research is needed to ensure that UK NHS guidance is being informed by country-specific studies (Wells and Tolhurst, 2021).

The critical review was also restricted by its reliance on a single researcher. The single researcher had to navigate both time and financial constraints, and as a result their ability to generate unbiased results may have been compromised. It would have been beneficial to employ additional researchers, including librarians and other colleagues in the field, to validate and corroborate searches and findings (Reisenburg and Justice, 2014).

Recommendations

There is a significant disparity in how the ANP role is utilised in care homes, both across the UK and internationally. The authors recommend that a strong national meta-analysis, SR-based study—that explores the impact that an ANP can have on the QOL of ageing, co-morbid, complex frail patient living within care-homes, who continue to remain high users of secondary-care—be conducted. Investment into research evaluating the cost of delivering this approach within UK care homes is also essential. Such efforts would further assert the practicality and cost-effectiveness of investing in the ANP role and help inform future guidance and budgetary concerns.

Conclusion

This paper has highlighted how the ANP role can enhance healthcare outcomes in frail older patients living in care facilities. It has indicated that the involvement of the ANP within the care home addresses the EHCH agenda (NHS England, 2022) and, in conjunction with the GP-alone approach, provides quality service provision for elderly frail residents within care homes. This provides further weight to the argument that ANPs help provide a more holistic approach to healthcare.

While this paper cannot prove whether the ANP role is superior to the approaches of multi-disciplinary teams, it does assert that the use of ANPs is equivalent to that of the physician-alone approach. Therefore, as the number of available GPs and geriatric physicians continues to decline, ANPs can be put forwards as a measure to, alongside GPs and the MDT approach, address the shortcomings in the current UK primary and secondary care workforce.