Examples of developing trained healthcare professionals to take on additional advanced tasks and skills or extended roles can be found globally (Dunn, 1997). Comparisons have been made between the UK trajectory and that of Europe and Australia, with recognition that particular countries, professions, specialties or healthcare services are at different stages of development in relation to models of advanced clinical practice. Maier et al (2016) and Pulcini et al (2010) noted that, while advanced clinical practice roles have varied, initial development is typified by a need to reconfigure services to address unmet need. Common examples are substitution in the case of a short supply of medical professionals (for example, as described by Coombes (2008) in the controversial piece titled, ‘Dr Nurse will see you now’) or to develop new ways of working, such as the shift from acute in-hospital health services to delivery of community-based healthcare. For example, the introduction of the Affordable Care Act in the US accelerated the use of advanced nurse practitioners in community-based, nurse-led clinics and public health initiatives (Cleveland et al, 2019).

For many years, reference has been made to ‘advanced clinical practice’ and ‘advanced clinical practitioners’, and attempts have been made by various countries and governing bodies to control the use of this title (Carney, 2016). For the purposes of this article and the research it reports, the term ‘advanced clinical practice’ includes references to alternate nomenclature related to different professional groups (eg, ‘advanced nursing practice’). It also encompasses references to the individuals that are undertaking the acts related to the practice itself (eg, ‘advanced clinical practitioners’ or ACPs), while noting that there are many different titles being used to describe these individuals (Leary et al, 2017).

In 2017, a number of UK-based professional bodies collaborated to create the Multi-professional framework for advanced clinical practice in England (Health Education England, 2017). This document sets out a definition of advanced clinical practice; the scope of practice and practitioners this applies to; and the standards and capabilities expected by those that practice under this title. The framework is structured around a ‘four pillars’ model of advanced practice—clinical practice; education; leadership and management; and research—which is commonly found in definitions and policy surrounding advanced clinical practice globally (International Council of Nurses, 2020). While this definition falls short of regulation, it has provided a benchmark by which education and training providers can label their products as leading to advanced clinical practice; employers can use to select individuals to work in advanced clinical practice roles; and individuals can provide evidence against to support their credentials as an ACP.

Educational and policy development at an international, national and local level (such as introduction of the aforementioned framework) has led to an increase in activity around advanced clinical practice. The NHS Long-term Workforce Plan (NHS England, 2024) echoes previous global ACP research, which has established this role as providing potential benefit to clinical effectiveness and innovation in reshaping health services to address population need. Ambitious targets have been set to expand the number of ACPs as a result, mirroring the global pattern of growth.

Previous research has highlighted significant barriers to the effective implementation of the role. (Duffield et al, 2009; Miller, 2009; Delamaire and Lafortune, 2010; Heale and Rieck Buckley, 2015; Thompson et al, 2019). The global COVID-19 pandemic has further strained the healthcare workforce, creating a significant challenge in recruiting and retaining staff. In a literature review conducted by the author, there was limited research found that focused on recording the direct experience of people working in ACP roles; what their expectations were regarding taking on these roles; and whether these were being realised. This has clear implications for the ambitions to grow and retain ACPs and realise their potential.

Method

This cross-sectional study uses a sequential, mixed-methods, exploratory design, in which themes identified during focus groups were used to construct a follow-up questionnaire. Using maximum variation sampling, the focus groups took place online and were examined via reflexive thematic analysis. The online follow-up questionnaire collected both quantitative and qualitative data. Exploratory data analysis (EDA) and reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) were employed to probe and visualise results, drawing findings together via narrative synthesis.

This research values the diversity of the viewpoints of ACPs and aims to give voice to their experiences. It takes a pragmatic, critical realist and emic approach to capture the ‘insider's view’. A reflective diary and thick description were used throughout the research to note the environment and interactions encountered during the research. This was done to record subjective reflections and explanations regarding the research process, and to develop understanding of the context in which this research has been situated. NVivo was used to store ‘sources’ (documents and information); ‘code’ extracts from sources; and organise these into ‘nodes’ (themes). Zoom was used to facilitate and transcribe focus group discussion. Qualtrics software was utilised for questionnaire data collection and analysis of results. While using these tools to systematically organise and record data and provide rigour to the research process undertaken in this study, they were deliberately not used to conceal the influence of reflexivity and the author's positionality in this research.

When considering ‘conceptual’ or ‘theoretical’ generalisability and the methodological choices made in this research, the aim was not to test against a hypothesis, existing concept or theory of advanced clinical practice. Through the use of a sequential design, the research has been able to draw upon focus groups to identify and construct themes relating to ACPs' own experiences of the role. Rather than being used to develop a generalised concept of the ACP experience, this article provides a report of the methods used so that these could be replicated for longitudinal research or for different, concurrent or more localised groups of ACPs (eg, in other countries or in specific organisations, services, or teams of ACPs). While it cannot be assumed that the results produced would be the same, this would allow for targeted, culturally relevant and context-specific interventions to be developed, to narrow any gaps identified between the expectations and reality of working in an ACP role.

The research question identified was: what are ACPs' expectations of the benefits in pursuing this role, and are they being realised?

This was addressed by asking:

Brown et al (2015) noted that use of mixed-methods research is appropriate in situations where the aim is to provide an account of both the nature and magnitude of a phenomenon. A single method in this research would not have adequately captured both the expectations (the nature) and whether they are being realised (the magnitude) in advanced clinical practice (the phenomenon being studied). A combination of methods was needed to address these aims; thus, a mixed-methods research design was chosen. Once the expectations of ACPs were understood within a particular context (using focus groups), an instrument (follow-up questionnaire) was developed to test the prevalence of these variables (ie, whether expectations are being realised).

Recruitment

Using the Multi-professional framework for advanced clinical practice in England (Health Education England, 2017) as a frame of reference for an ACP population, UK participants were recruited to this study via social media and established ACP networks (via Twitter, Facebook, the Association of Advanced Practice Educators UK and University of Essex's ACP news forum). All social media posts and emails distributed through ACP networks asked people to distribute the invitation to their own relevant contacts.

There are no nationally and publicly available verifiable figures relating to how many ACPs are practising. As noted in previous research, identification of ACPs is fraught with difficulties related to the variation of role titles being used (Leary et al, 2017). A target figure for sample size was set at between 229–261 participants, with a confidence interval of 95% and 6% margin of error, taking into account a previously reported East of England regional number (1573) and, from this, an estimated national number (11 000) of ACPs and trainee ACPs (Health Education England, 2021).

The inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) were used to identify eligible participants from respondents to a recruitment questionnaire. The invitation to participate asked individuals to return, by use of a ‘one-click survey’, an expression of interest. Further information about the research was then displayed, along with a consent form to complete if potential participants wished to proceed. By completing the online consent form, participants were then re-directed to the questionnaires on Qualtrics. No data were retained for those that did not consent to participate or for those that were not eligible to participate according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

| In a role/job title identified by the participant's employer as being, or training to become, ‘an advanced clinical practitioner’ |

| In a role/job title that fits the description of being, or training to become, an ‘Advanced clinical practitioner’ according to the Multi-professional framework for advanced clinical practice in England (Health Education England, 2017) |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Not currently employed within an ‘advanced clinical practitioner’ or trainee ‘advanced clinical practitioner’ role |

| Suspended, excluded from practising as an ‘advanced clinical practitioner’ or undergoing investigation for Fitness to Practise |

| Not willing to participate in this research, which includes completion of online surveys and a potential invitation to participate in a focus group |

From previous research conducted in this field, it is known that there are a range of titles used in advanced clinical practice, which can lead to over-emphasis on certain ACPs and the neglect of others within this diverse community. The use of maximum variation for purposive sampling attempts to capture the most diverse range of participants from the population, which can be used to check if a core value or theme occurs across a wide range of cases. The recruitment questionnaire generated data regarding the ACP population, which were categorised (eg, job title, professional background, length of time in the role, pay scale, location, field speciality). The sample for the focus groups was cross-checked with this data to ensure there was a diverse range of participants selected from each category in each focus group to achieve maximum variation.

Some 219 people consented, met the inclusion criteria and completed the recruitment questionnaire. From this population, 17 participants engaged in one of three focus groups. Some 230 people consented, met the inclusion criteria and responded to the follow-up questionnaire.

Focus groups

The focus group was semi-structured, with use of a topic guide (Table 2), and facilitated by the primary researcher. Participant information, including guidance on using Zoom, was provided in advance of the meetings. A set time limit of 90 minutes was used, so that participants did not become exhausted or disengaged. The focus group began with an introduction to ensure participants were aware of the aim and purpose of the research and how it would be conducted and disseminated. Before confirmation of their consent to participate, participants were also reminded of the support systems that are available to them should the research raise any questions, issues or concerns. The trigger questions that followed explored the research question and concluded by summarising topics discussed, to confirm that there were not any other comments or areas participants wanted to be noted. Transcripts automatically generated by Zoom were read, corrected and coded by repeatedly referring back to the recordings of the focus groups. This allowed for familiarisation with the data, which then underwent a recursive process of reflexive thematic analysis, as described by Braun and Clarke (2020), to identify, define, clarify and name the themes generated. The reflective diary and thick description were used to explore the impact of contextual influences within the key themes identified, refining or clarifying them further where needed.

| Section | Content | Guidance notes |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Aims, purpose, data storage and intended dissemination, role of facilitator, sources of support | Remind participants there are no right or wrong answers |

| Close with checking consent before proceeding | ||

| Trigger questions | Engagement | ‘Can I first of all ask everyone to introduce themselves and say what made you choose to pursue your role as an advanced clinical practitioner?’ |

| Exploration | ‘Other than enhanced patient care and good quality outcomes for your patients, when embarking on your current role/training as an advanced clinical practitioner, what did you hope or expect from the role?’ | |

| Probing | ‘Give examples’; only to be used if prompting or clarification is required, noting if these have been acknowledged in previous research (eg, pay, job satisfaction, remaining clinical) | |

| ‘Has it encouraged/allowed you to stay working longer in the NHS than you otherwise would have done?’ | ||

| Exploration | ‘What future aspirations do you have in your role as an advanced clinical practitioner?’ | |

| Probing | For example (prompt if needed), ‘If someone was to ask you what you hope to achieve in 1 year or 5 years' time (or longer), what would this be?’ | |

| ‘How do you hope and expect your current role to change (if at all) in the future?’ | ||

| Member checking | Summarise discussion | Ask if there are any other key topics that the participants believe have been missed. This will be repeated until the group believe there are no further key themes to be identified from their discussion |

Follow-up questionnaire

The themes identified from the focus group were used to search for relevant validated questionnaires to answer the research question. However, the range of themes generated from the focus groups were not able to be identified in a single validated questionnaire. Although a combination of validated questionnaires could have been used, this presented a risk to the integrity of the research (by combining and using them in ways that were not originally intended) and potential participation (by creating a very long and inconsistently formatted questionnaire). The newly developed follow-up questionnaire needed to answer the following research questions:

Supervision meetings undertaken during the author's PhD allowed for ‘debriefing’, as described by Zhou (2019), where the new questionnaire was discussed to explore the relationship between the items included, the themes taken from the focus groups, and the underlying construct. A pilot study of the follow-up questionnaire was undertaken to identify and address any technical issues with administering the questionnaire and to gather opinions on whether the questionnaire captured the key themes identified by the ACPs from the focus group. Pilot study data confirmed that the questionnaire would normally require no more than 30 minutes to complete and that the questionnaire flowed as expected and displayed questions accurately. In all but one question, the pilot study confirmed there was an appropriate range of options for response (the one question where this was not the case was amended as a result). The pilot ACPs' responses, plus 60 random responses (generated by Qualtrics), were used to run a dummy analysis using a pre-planned schema, which incorporated EDA (for closed questions) and RTA (for open questions), providing reassurance that the planned mixed-methods analysis would achieve the intended research objectives.

Findings

The focus group analysis initially identified four ‘context codes’, providing a basis or background to the themes generated and how these related to the research questions being posed:

The context codes encompassed both positive and negative experiences and perceptions the participants had about the expectations of the role, which was also reflected in the themes generated from the focus groups (Table 3). These themes were used to construct the follow-up questionnaire.

| Themes (top level codes) | Stories including sub-themes (child codes) |

|---|---|

| Clinical | Advanced clinical practice allows healthcare professionals to remain clinical/patient facing, while also allowing them to focus on non-clinical activity duties/tasks |

| Full knowledge, skills and experience (KSE) | Where it works well, advanced clinical practice allows practitioners to use their full KSE, including their specialist background, and become a ‘go to person’ or font of knowledge and expertise to educate, advise and support others. Within this, there is autonomy to use this wealth of knowledge, skills and experience (tapestry of KSE) to address the needs of their patient/client group/service provision. Advanced clinical practice also provides an opportunity for personal professional development and the education of others through succession plans and making the most of the knowledge, skills and experiences |

| Leadership in quality improvement | Advanced clinical practice includes leadership in quality improvement to develop services, achieve benefits for patients, work collaboratively and develop staff. This is also used to deal with ‘frustrations’ with services—allowing problem solving and the reshaping of services to make them more effective. This includes acting as a consistent and coherent presence within their service, where other staff may move in and out, and bringing several different tasks/processes together. This is seen as positive for the patient and for staff development in maintaining the safety and the quality of patient experience |

| Career progression | The advanced clinical practitioner role can provide incentives and opportunities for career progression (including their scope of practice, moving up the hierarchy and financial implications for pay, grading, pensions and costs of working) that reflect their level of experience and responsibility. The role also presents as valuable and satisfying, and not harmful to career and pay or grade trajectory |

| Policy, vision and structure | The advanced clinical practitioner role works well when there a clear, coherent direction, vision, and support structure for the role that is shaped by the policy, vision and organisational structures that are in place, (outside of the direct control of the practitioner themselves, eg at an organisational level). This includes how this maps to an advanced clinical practice standard or quality assurance process. This needs to be agreed at the beginning, where buy in and support (including role models, championing and supporting the advanced clinical practitioner role) at all levels has been addressed. Advanced clinical practice is, and should, continually evolve. However, it can be impacted by local factors, including lack of understanding of the role and service demands. This works best where teams have become well established and long-term investment has been secured. |

Demographic data collected in the follow-up questionnaire revealed that respondents came from a diverse range of geographical and clinical speciality backgrounds. Job titles varied, although were primarily generic (ACP or trainee ACP), with some including reference to their profession or speciality:

Clinical/patient-facing

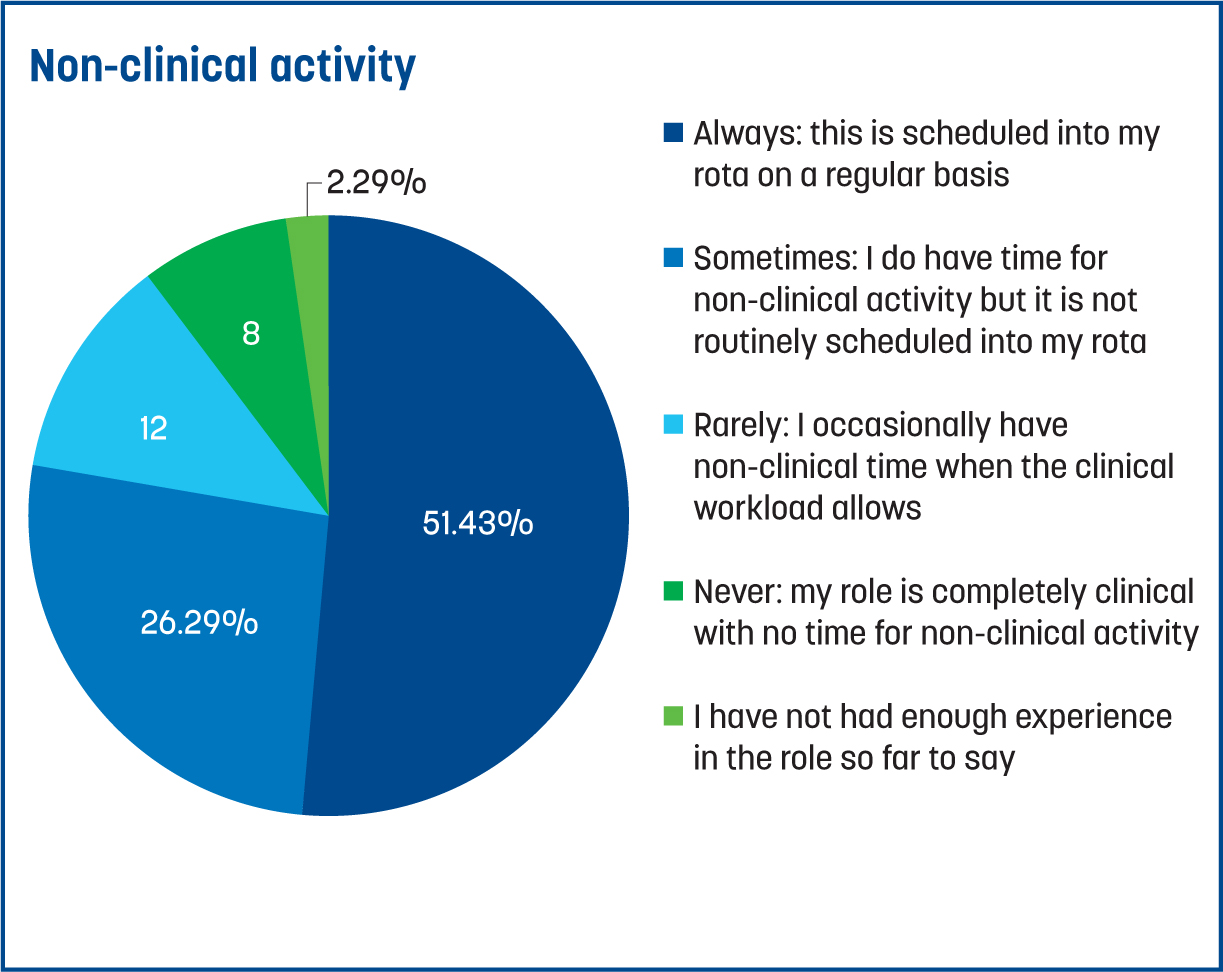

Unsurprisingly, nearly all participants (99%) noted that their role involves clinical work on a regular basis (eg, normally every week). In comparison, only 51% said they undertook non-clinical activity as part of their regular rota (Figure 1). When asked about the balance between clinical and non-clinical activity, respondents overall said there was too much clinical and not enough non-clinical work. The variance from the mean for non-clinical was greater, highlighting there is a broader range of experience in time afforded for non-clinical activity (most often, this was impacted by the pressures of clinical activity). Many also noted they undertook non-clinical activity for their ACP role in their own time. Those that said their role partially fits with the Multi-professional framework (Health Education England, 2017) and addresses some, but not all, of the four pillars were more likely to say their role was entirely clinical, with no time for other types of non-clinical activity. The comment given below by one of the respondents reflects a common experience of ACPs who responded to this research:

‘I do feel that I am very clinical-heavy within my role. While I understand that is because the NHS is facing a large demand and we need clinicians to see patients, if I had more non-clinical time, it would allow me to have some breathing space to focus on other areas or projects that could improve our service.’

Full knowledge, skills and experience

The majority of respondents believed that they were able to use a range of knowledge, skills and experience (KSE) in a typical week in their ACP role. This was likened by the author to a ‘tapestry’, where participants' scope of KSE (represented by differently coloured threads) had been gained over time and are woven onto the strong structure of their professional background and training (strong-meshed cloth). This results in some aspects of their KSE being hidden (messy warp threads and the supporting structure of the strong cloth), but which are vital to the integrity of the health service or interventions ACPs provide.

Some participants noted their work across several different areas, which allowed them to ‘gain valuable insights’, and recognised the ‘transferable skills’ they were using from their base profession (eg, nursing) and other roles they had previously held. In ranking whether they thought their role and the KSE they drew upon in their role was mostly ‘generalist’, ‘specialist’ or a ‘mixture of the two’, ‘generalist’ was most often listed first, followed by ‘a mixture’, with ‘specialist’ being placed last. Primary care (the largest group to respond to this questionnaire) fitted this pattern most closely. There was, however, significant variation geographically, where, in some areas, this ranking was reversed.

The majority (74%) thought they were used as a point of reference for advice and the answering of queries and for colleagues to seek support. The majority (81%) believed, to some extent, that they had autonomy in clinical decision-making in their ACP role, in which they did not always need to seek approval from others. However, there were particular groups and policies in which limited autonomy was highlighted (eg, restrictions on prescribing of certain drugs by paramedics). Around one-third of participants said they would like to have more opportunity to engage in professional development for themselves and others.

Leadership in quality improvement

Respondents reported that involvement in leading on quality improvement was relatively modest, with the mean being 5.54 (on a sliding scale in which 0 was ‘not at all’ and 10 was ‘all the time’). The amount of variance and the 35% of respondents who reported less than the median to this question suggests leadership in quality improvement activity is patchy or poorly planned, as typified by the response below:

‘No firm plans around job role makes it difficult to realise the full potential of the role. Reluctance to develop new services or new models of healthcare is a real challenge.’

Some 80% believed they contributed to continuity of care, and 88% believed they were a consistent and coherent presence in their team. The same proportion (88%) also believed that they had helped to reshape a service to make it more effective, although the mode (48%) thought this could go further through better use of ACPs. The majority said that patient safety and experience is a key focus of their role and that they do feel they make a difference. There was, however, 12% who reported that this was not part of their role or that they do not feel they make a difference to patient safety or experience.

Career progression

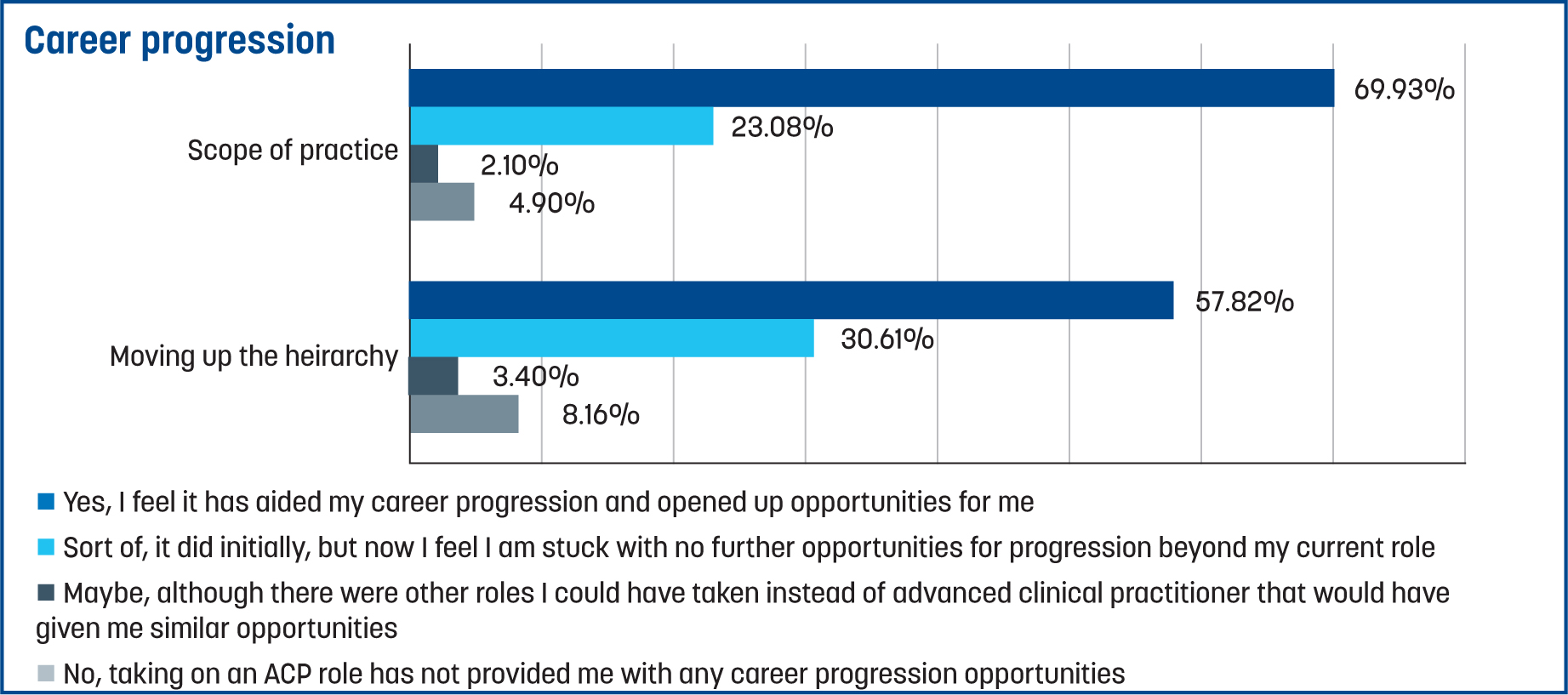

More respondents than not believed that taking on an ACP role had aided their career and opened up opportunities for them. However, around 25% now felt ‘stuck’, with no opportunities to expand their scope of practice or progress beyond their role (Figure 2). One participant noted, ‘It's given me career progression to this point, but trying to progress further after significant experience has been a challenge.’

Out of all that responded, 84% had received or were expecting to receive a pay rise; there were some groups where this was more common than not (eg, those that had a portfolio career, fully met the Multi-professional framework (Health Education England, 2017) definition or had completed an MSc or a credentialling programme in advanced clinical practice). Just over half (56%) said that taking on the ACP role had a positive impact on their financial status (eg, pension benefits, opportunities for other paid work, or reduced commuting costs). Results were broadly distributed regarding impact on work–life balance; the mean response was marginally more positive than not. Some 85% reported that the ACP role had had a positive impact on their job satisfaction.

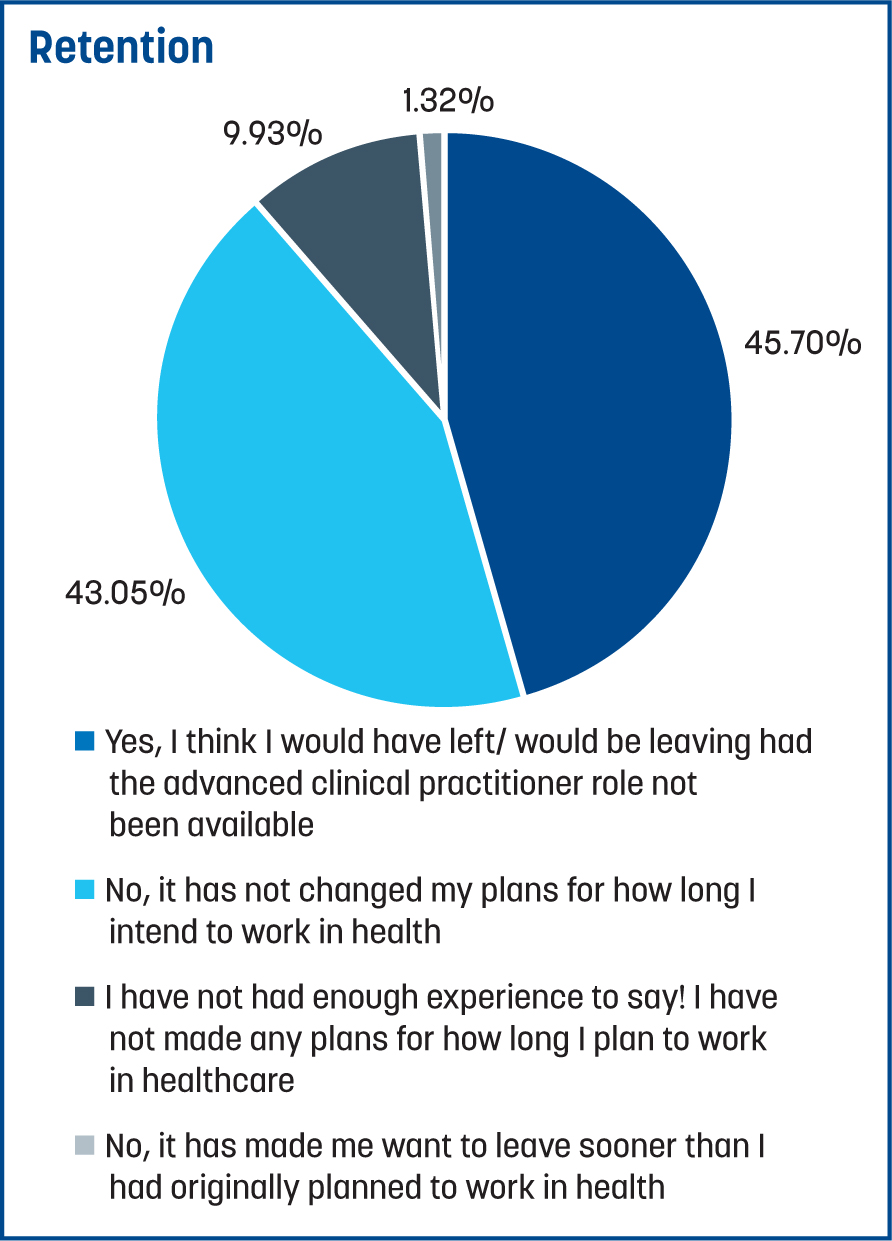

While 93% said they always, mostly or sometimes feel valued in their role, only 46% believed their salary appropriately reflected their level of experience, responsibility and scope of practice in comparison to others working in their service. Patients and colleagues were cited most frequently as people who helped ACPs to feel valued, and feedback was the most common activity contributing to this. The mode (46%) said that taking on an ACP role meant they had stayed working in health services longer than they would have done if this role had not been available (Figure 3). For example, one respondent noted that:

‘I feel my role is very unique and it has been a saving grace; being able to fully meet the four pillars has been a dream, and I am much more motivated to continue working in healthcare as a result.’

Another noted:

‘This is where I want to be until I retire—I get to spend most of my days with patients, making a difference, and I get to influence positive change within our organisation. NEVER been as satisfied with my job as I am now.’

Policy, vision, structure

Only 16% believed there was good understanding among staff about the ACP role and what they can do. Some 64% said they were aware of the advanced clinical practice lead in their organisation; however, only 39% felt that their lead did a good job of acting as a role model or championing advanced clinical practice. Less than half of the respondents (43%) reported feeling well-supported in their employing organisation (eg, within their team or through other mentors, role models or leaders).

A substantial number (40%) said their employing organisation did not have policies, structures and processes in place to support the effective implementation of ACP roles. The same proportion (40%) also reported that their organisation mapped the ACP role to policies or standards in principle, but that this was not universally applied or had not been fully implemented yet. A further 20% said their organisation did not quality-assure the role. There was variation in answering whether their organisation had ‘bought into effectively implementing the ACP role’. One respondent noted:

‘My role as ACP was pushed by myself, working as one with relevant qualifications. That is my experience of the role where I work locally: nurses doing the job campaigning for better pay and correct job titles based on the framework. There is no strategy which exists; no money for expansion.’

The majority did, however, believe there was support and flexibility to evolve the ACP role in their organisation, and 76% believed their organisation had committed to long-term investment in the role.

There was no pattern identified as to whether the role was being operated in a localised or consistent manner across employing organisations. As a broader judgement regarding the policies, governance and strategic oversight of advanced clinical practice, respondents were asked to rate this at a local, regional, and national level. The majority of responses (83–84%) fell under ‘needs further development’ or ‘not addressing fundamental aspects’ at all levels.

Summary question

Finally, respondents were asked about their overall experience of the ACP role so far. The mean response was 6.66, with a standard deviation of 2.23 (on a sliding scale, in which of 0 was classified as ‘my expectations have not been met at all’, 10 classified as ‘my expectations of the benefits of the role have been exceeded’, and 5 classified as ‘the role is delivering as I had expected it would’). Only 17% scored 4 or less, suggesting that, for the majority of ACPs, their expectations for the role had been met or to some extent been exceeded.

Limitations and potential for future research

This research has been conducted by a sole researcher at a particular point in time on the evolution of the ACP role in the UK. While efforts have been made in this study to capture a diverse group of ACPs' experiences, the lack of contemporary published data on the demographics and characteristics of ACPs limits the ability to identify how representative the respondents in this research are of the broader global ACP community. This is likely to vary considerably in different healthcare contexts, where the findings from this research may resonate more directly with some ACPs more than others. It is acknowledged that limited resources, time, use of online methods, and participant availability could have constrained maximum variation and may have led to voluntary response bias (ie, those that chose to participate are different in some ways to the general population of ACPs). Further investigation of ACP communities may allow for more tailored research to be conducted. Research conducted at a time in which the context of advanced clinical practice is clearer would facilitate more targeted initiatives to address expectations (eg, within a specific geographical region, organisation, service or team). Longitudinal and localised research, which continues to evaluate whether gaps between ACPs' expectations and the reality of working in the role are being narrowed by policy initiatives (such as introduction of regulation) or events (for example deployment of ACPs post-pandemic), is needed for effective and sustained positive change to occur.

Conclusions

The aim of this research was to provide an opportunity for the experiences of people working in ACP roles to be captured. Through greater understanding of their perspective on the expected benefits of the role and the reality of working as an ACP, any gaps between expectations and reality can be highlighted. This new knowledge can be used to better inform ACPs, potential ACPs, and those that provide advice, support, training and education to these healthcare professionals about the reality of working in this role. This study has added ACPs' perspective and endorsement to the desire for the ‘four pillars’ definition of advanced practice to underpin their work:

This research has identified gaps regarding the experience of the ACP population and the expectations they hold regarding the benefits of the role, which has implications for recruitment and retention for ACP roles. Barriers to recruitment need to continue to be reviewed to ensure a diverse population of staff are drawn into performing this role. The data from this study have revealed that a large number of ACPs take on this role at an advanced stage in their career and, therefore, may be looking at different options for career progression, career change or retirement.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are made from studying the gaps identified between ACPs' expectations and their lived experience of the role.

Ringfence non-clinical activity

There needs to be a balance of clinical and non-clinical activity to attract and retain ACPs. This would be aided by ringfencing time for non-clinical activity. Clear direction on which activities are expected or are not to be performed in this time is required—for example, rostered non-clinical time should not include administrative duties where these relate to clinical patient management. Use of ACP roles as substitution (eg, for medical colleagues) risks narrowing their scope of practice.

Continuing professional development and supervision

ACPs draw upon a tapestry of KSE, but do not always feel like this is understood, recognised, or used as effectively as they could be. A targeted campaign is needed to increase the awareness and understanding of what ACPs are and what they can and should be doing. These professionals are not receiving enough opportunities to engage with professional development for themselves or others. Receiving feedback made ACPs feel valued in their role, which could be enhanced by more effective access to supervision.

Opportunity for leadership

Enhanced opportunities for ACPs to engage in leadership are needed. This could be enabled by ACP leads, who role model, raise awareness of the advanced practice role and create opportunities for leadership. Alongside national or international policy development and support, more direct action may be needed to change the localised organisational culture to allow ACPs to design and lead, rather than just deliver quality improvement projects. ACPs need a place at the table when policies and new initiatives or projects are being planned. They should be recognised as wielding power to influence and impact the success of projects to reshape services by using multi-disciplinary teams to enhance continuity of care, patient safety and experience.

Career plans

For the majority of ACPs, moving into this role has provided personal benefits in terms of pay, diversifying their scope of practice, and moving up the hierarchy. However, the localisation of how advanced clinical practice has been implemented means that clear and realistic career pathways for movement into and onward from ACP roles need to be provided. Honest, objective advice needs to be given at an individual level to enable that person to weigh up potential benefits and decide if pursuing or staying in an ACP role will be the right choice for them and for the organisation or service in which they intend to work. This includes being clear about the extent to which the roles are expected to be generalist/specialist and substitution/supplementation. This may require further clarification and direction about what is acceptable or desired in the growth and implementation of ACP roles.

Standardisation

While there is evidence of progress being made, there is a significant amount of work needed to ensure the right environment for effective ACP roles to thrive. Efforts to standardise advanced clinical practice have begun, but these need to be further embedded and evaluated for their impact. From this research, there is some evidence that initiatives such as the Multi-professional framework (Health Education England, 2017) are having a positive impact (eg, on pay and ‘quality assurance’). It also shows that there are still significant areas of the ACP population where this has not been fully implemented yet (in primary care and with AHPs). There is a risk that initiatives to standardise continue to proliferate without evaluation of their success. One respondent noted: ‘I think there is a journey still to realise the full benefits of the ACP role.’