The advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) role was developed in response to a variety of factors. First, it was established to advance the nursing profession. Second, in relation to the NHS Long Term Workforce plan (NHS, 2023), it was expanded to address the shortfall in doctor staffing numbers, the increasingly complex clinical demands on healthcare staff and the growing needs of the UK's ageing population (Reynolds and Mortimore, 2018). Since the formal recognition of ANPs by the International Council of Nurses, the role has been adopted across many departments and clinical specialties (Htay and Whitehead, 2021).

ANPs make critical decisions regarding risk and patient safety (Health Education England (HEE), 2017). These practitioners commonly work in acute settings such as emergency departments (EDs), urgent care centres (UCCs) and minor injury units (MIUs). In these settings, timely decisions are required, often with limited information and conflicting facts (Lyneham et al, 2008). Several studies have identified how clinical complexity has increased the necessity of practitioners making quick decisions about the risk and safety of patients (Burman et al, 2002; Ritter, 2003; Bowen, 2008; Rasmussen, 2012; Pirret et al, 2015).

The focus on risk in healthcare is essential, as the consequences of poor management and subsequent compromise of patient safety can have critical and life-threatening consequences for patients (Burton and Wells, 2016). Well-publicised clinical mistakes and high-profile incidents have led to calls for stricter controls and monitoring of clinicians through protocols and evidence-based guidelines to ensure that care is standardised, effective, of good quality and safe (Goodwin, 2018). Patients are also increasingly aware of poor practice through access to information and support from social media (Househ et al, 2014). This heightened focus on patient safety has led to a decrease in public trust and faith in healthcare provision (Hutchison, 2016), and increased awareness of the fallibility of clinicians (Ilangaratne, 2004).

Clinical risk is traditionally managed through standardised policy-driven, evidence-based guidelines (Valderas et al, 2012; NHS Digital, 2018). Global and national guidelines, such as World Health Organization's clinical guidelines on trauma care, are a central component of a comprehensive and coherent governance and policy framework for the provision of healthcare (Mock et al, 2004; Bull et al, 2020). Policymakers view such guidelines as a tool to close the gap between what clinicians do and what scientific evidence supports, with the overall goal being to achieve consistent, efficient and safe patient care (Pereira et al, 2022).

ANPs can find themselves caught in a grey area between the recommendations of policymakers and guidelines, and the complexities of patient risk and clinical situations. Understanding ANPs' experience and their personal perspectives of risk may be beneficial in helping policymakers understand the dichotomy of this area.

Current evidence regarding managing risk and patient safety is concentrated in specific areas such as paediatrics, psychiatry and surgery. At present, little information exists regarding the experience and reality of how ANPs manage risk and patient safety in acute settings. Thus, the ANP experience of the management of risk and patient safety warrants direct investigation to illuminate, explain and understand this critical but illusive crux of advanced practice. This understanding will help inform educators, employers and policymakers, and may also enhance the safety of patients.

Methods

Phenomenology is an inductive, qualitative research method for investigating the lived experience of a phenomenon; it can be used to understand what something is like for an individual (Leedy and Ormrod, 2015). This method assembles experiences to make it easier for others to understand the subjects' lived experience and cultivate a worldview of an area they do not have personal experience of (Patton, 2002; Borbasi and Jackson, 2011).

Heideggerian interpretive phenomenology focuses on consciousness and essences of phenomena (Finlay, 2009). The author's choice to use interpretive rather than descriptive phenomenology lay in the assertion that as an ANP, they are an ‘insider’ and could potentially enrich the interpretation of the data beyond pure description (Kanuha, 2000; Asselin, 2003).

Recruitment of participants

Participants were recruited through purposeful sampling of ANPs who identified themselves as having experience with managing risk and safety in practice (Creswell and Clark, 2011). Purposeful sampling is commonly used in phenomenology to acquire thick descriptions (Hollywood and Hollywood, 2011; Sabo, 2011; Bedwell et al, 2012; Converse, 2012). Between two and 10 participants are considered sufficient in a phenomenological inquiry (Giorgi, 2003). A total of 10 ANPs were selected; this number protected against participant drop out. Recruitment took place across three settings: an urban ED, a suburban UCC and a collection of rural MIUs. Sites were varied in the hope of potentially achieving more variable results and a greater breath of enquiry (Shenton and Hayter, 2004).

Data collection

Data were collected in three phases over 10 months alongside the researcher's journal:

Multiple research stages allowed for the author to build trust with the participants and enhanced the credibility of the gathered data by allowing for a variety of topics to be discussed (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). This form of reflective storytelling allowed participants to discuss their perspectives and lived experiences (Craig and Smyth, 2011). Gibbs' (1988) reflective cycle, which offers a flexible simplistic structure for participant-led interviews and written reflections, was implemented in the data collection.

It is important for qualitative researchers to situate themselves in the research (Ely et al, 1991). As an ANP with pre-understanding of the area being studied, the author can be considered an insider and fulfilling of this criterion (Coghlan and Casey, 2001). Such positionality can have implications for the trustworthiness of the study, as it may lead participants to being more ‘open’ with insiders (Edwards and Talbot, 1999; Asselin, 2003) and provide a greater depth and breadth of data (Kanuha, 2000). Conducting this study required respect, self-awareness of the author's presence and the potential effect on the research on the participant (Bonner and Tolhurst, 2002; Mercer, 2007; Bourne and Robson 2009). The author ensured they remained focused and non-subjective through self-reflection, reflective journaling and regular supervision meetings.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was sought and gained through the university's research ethics committee on 29 July 2016; informed consent and participant information sheets were provided. Research governance and risk assessment forms were completed.

Data analysis

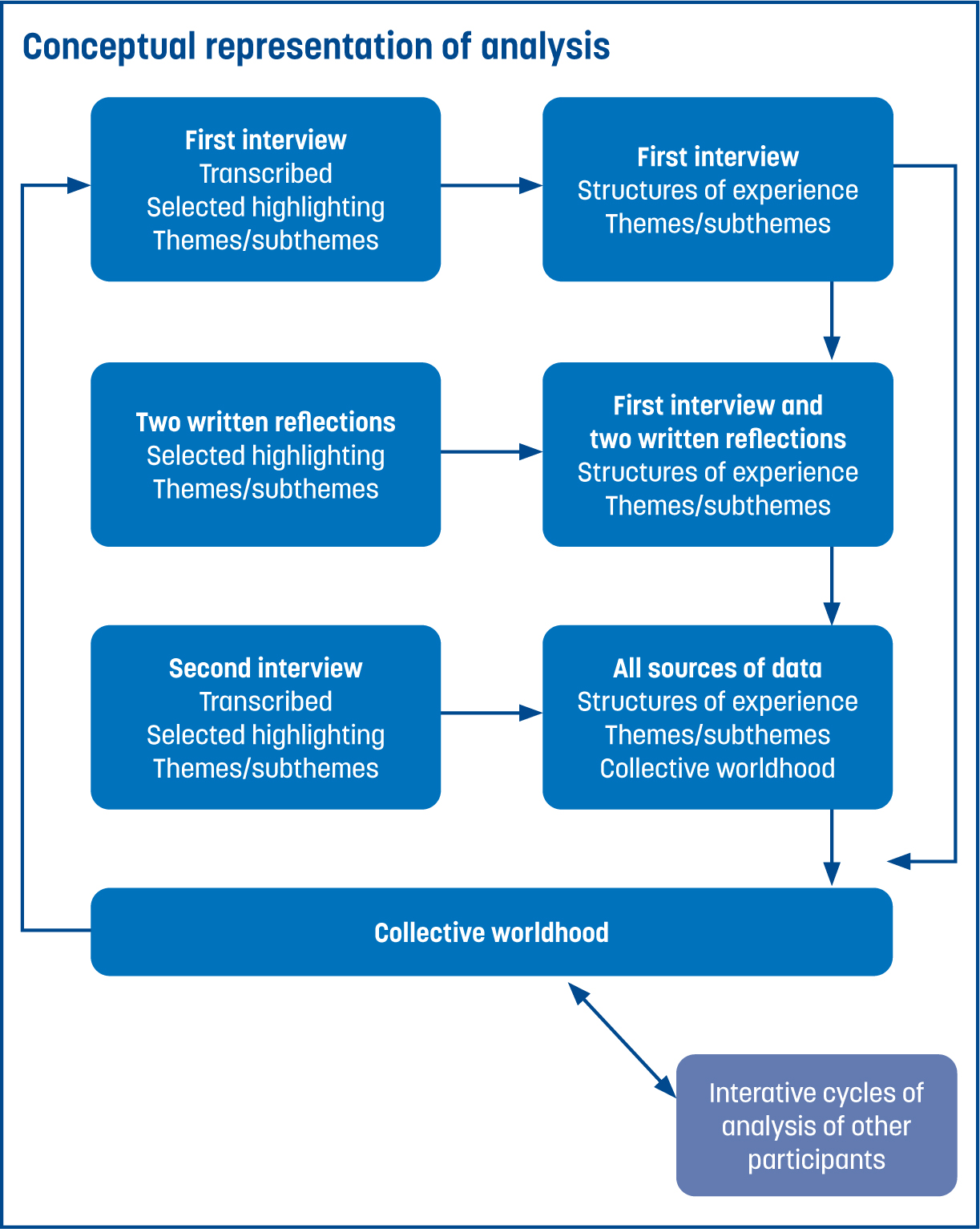

Van Manen's (1997) step-by-step data analysis afforded clear guidance to the stages of analysis required. This approach has been frequently used in similar studies (Donnelly and Wiechula, 2006; De Witt et al, 2010; Smythe and Spence, 2012; Glenn et al, 2015) and was used to analyse the collected data. NVivo 11 software assisted analysis. Figure 1 demonstrates this process.

In line with Van Manen's (1997) approach, each interview was transcribed verbatim and read in its entirety to grasp overall meaning. Journaling, recording ideas and ongoing comparative analysis enabled iterative continuous analysis. NVivo 11 software assisted reading and re-reading transcripts line by line, and the coding and selective highlighting of relevant quotations. Units of meaning derived were individually interpreted and then clustered to form subthemes and themes for each participant. Participants' lifeworld themes were presented, interpreted and interpretively described (Figure 2). All individual lifeworld themes were collated to form a collective worldhood of the lived experience of all participants. This process involved cross-analysis between the different data sources for each participant, including the cross-tabulation of themes and subthemes of each lifeworld to derive collective subthemes and themes for the collective worldhood of the experience of managing risk and patient safety in practice.

Results

Participants managed risk and safety through being continuously aware and balancing probabilities of potential risks, according to contextual interpretations, at specific moments in time. Coping involved integrating available information with existing knowledge, navigating through emotional instincts, perceiving capacity and conducting shared negotiating with others. Supported experiences of risk were an opportunity to expand knowledge and advance practice safely. The collective worldhood themes were:

Environment

ANPs work in a time-sensitive environment. They manage and cope through balancing the probabilities of risk and safety with their capacity to cope at any given time. Risk is constantly changing according to place, time and perspective; thus, related decisions must be understood in this context. Judgements are made based on snapshots of time. A participant likened their workplace to a ‘conveyor belt’, which conveyed the relentless flow of patients. This metaphor suggests a constant pressing on of time and an overall lack of control. For these practitioners, risk management, in an environment that values objectivity over subjectivity, leads some to working around protocols/guidelines for the benefit of patients. Blind adherence to guidelines, rather than interpretation for individual patients, can restrict practitioners and could potentially push them down the incorrect treatment pathway and outcomes that are not in the best interests of patients. As one participant said:

‘Fixed protocols really don't fit the majority of patients. Very few patients will fit a very specific algorithm.’

Organisational targets and healthcare priorities can muddle risk navigation and cloud clinical judgements. Guidelines being followed defensively to safeguard professional risk can expose patients to new risks, such as unnecessary referrals, tests or hospitalisation.

Patient

Patient assessment involved rapid snapshot judgements based on a dynamic visual assessment. As described by one participant:

‘I like watching somebody walk in. It's not just looking, it's not even having a conversation with somebody—you've got to take the whole picture.’

Risk is negotiated according to perception, perspective and the risk-tolerance of all stakeholders. This involves care, trust-building, communication and building rapport with patients. Perspectives of risks do not always correlate; some patients can be anxious about issues that appear minor to a practitioner.

Coping

Coping with risk involves having an intuitive awareness, including being aware of the capacity of others (patients and colleagues), and their level of understanding and risk tolerance. Detection of risk provokes feelings of discontent, worry and concern, which then compels action, such as information seeking, safety-netting, sharing the risk and flagging it to others.

Participants described the security of managing risk safely ‘beneath the wings’ of more experienced staff and the clinical support of medical colleagues was described as a ‘safety blanket’. Effectively coping with risk enables the practitioner a sense of safety, resolving to positive feelings of being happy, satisfied, confident and self assured.

One participant described coping with this risk at critical times as:

‘When the wheels come off, you go into shock. It's only the central organs working. Intuition is what you rely on, instinct is all you've got. You're working on non-verbal cues. You're bringing other people in. We use other skills.’

Mood

Coping with risk is done so through emotive moods, such as being scared, because it sharpens one's awareness. Emotions were illuminated to be both drivers and barriers to practitioners' capabilities of coping with risk. As described by one participant:

‘If you're not worried, if you don't ever reflect and think back and think, oh, could I have done more or whatever, that's just not very good. But on the other hand, it's not good if you become anxious and you're worried all the time about your decisions. That's not healthy either.’

Feelings that may benefit practitioners, such as competence and confidence, were mirrored by feelings that may inhibit their capacity to work, such as feeling overly risk adverse or ‘fuelled by fear’. Feelings of exhilaration or being ‘on the edge’ may increase the potential for cavalier risk-taking, and innocuous moods, such as boredom, may lead to a complacent approach and lack of care. As described by one participant:

‘Nerve-racking is an area of growth. When you're slightly stressed and a little bit nervous, it means that you're probably pushing your scope of practice enough.’

Knowledge

Risk was found to emerge from a knowledge deficit. This presents as a sense of not knowing, the unknown, something missing or not yet understood; thus, residing outside of the comfort zone of firm knowledge. Indeed, participants' experiences of risk often led to them identifying a learning need and an opportunity to develop and advance their ANP practice. The key to advancement of practice was found to be in embracing and facing fears of what was not known, accepting the inevitability of risk and uncertainty, and taking ‘safe risks’ based on probability by using available resources.

One participant described:

‘You can only start advancing in practice if you step out of your comfort zone.’

Discussion

Policy–reality gap

The environment theme illuminated a conflict between clinical guidance and the reality of managing risk in practice. Traditional approaches to managing risk and patient safety in practice are policy-driven, and evidence-based guidelines are typically considered vital for safe, quality, cost-effective and standardised care (Department of Health, 2016; NHS England, 2016; HEE, 2017). Guidelines aim to increase effectiveness, minimise risk, avoid unnecessary testing and provide comfort and safety for practitioners (Snyder and Weinburger, 2014). However, systems aiming to enhance safety can introduce risk of over-investigation, over-admission, increased costs and unnecessary hospital transfers (Ghosh et al, 2012; Carayon, 2016). Conflict between guidelines and clinical context has been highlighted in other studies (Kramer and Schmalenberg, 2008; Benner et al, 2011).

The findings of this study also align with wider literature that reported that nurses use ‘work-arounds’ beyond practice guidelines for their patients' best interests (Stewart et al, 2004; Benner et al, 2011). While rule-breaking for the greater good relates to positive deviance containing elements of innovation, creativity and adaptability, it involves risk for the nurse (Gary, 2013). Naylor et al (2016) referred to an implementation gap between policy-driven strategies to enhance patient safety and the realities of what happens in practice.

Indeed, clinical and educational policies and guidelines must be applicable to the reality of practice, for both patient safety and the wellbeing of practitioners. If defensive practice is a by-product of practitioners finding it difficult to cope with risk safely (Gary, 2013), inadequate risk management could be seen as perpetuating a loss of patient confidence and trust, particularly in the wake of increasing public accountability.

Intuiting risk

Within the ‘mood’ theme, participants described their ‘gut-feel’, ‘intuition’, ‘inner voice’ and ‘instinct’ as tools for assessing risk and safety.

Links have been made between intuition and risk in the literature (Perez and Liberman, 2011). Bowen et al (2014) found that senior clinicians used a high level of intuition to effectively manage clinical risk. Being a risk-taker was identified by Miller (1995) as a characteristic of intuitive nurses, encompassing the willingness to act on intuition, client connection and an interest in the abstract. Sajjanhar (2011) concluded that guidance combined with expert intuition is invaluable and identified novice clinicians' reliance on guidelines and second opinions to achieve ‘safe’ decisions. Aligning with participant experiences, Perez and Liberman (2011) identified that intuition requires supportive networks for mentorship through risk-taking activities.

Resoluteness to pursue the awareness of risk or uncertainty was a key feature in how anticipated risk was managed for these participants. Stolper et al (2011) described an intuitive gut-feeling monitoring process as an effective component in reducing risk. According to Engebretsen et al (2016), dealing with uncertainty in emergency care is unavoidable and rather regrettable if attended to in a systematic and self-conscious way. Aligning with participant experiences, Perez and Liberman (2011) identified that intuition requires supportive networks for mentorship through risk-taking activities.

These findings illuminate non-linear processes in supporting practice involving risk and patient safety. Studies exploring the nature and use of intuition on every level and in every setting are imperative (Robert et al, 2014).

Emotional instinct

These findings also illuminated the use of emotional instinct, which was a thread through both the ‘mood’ and ‘coping’ themes. Clinical decisions are often made in challenging contexts that require clinicians to manage their emotions (Lerner et al, 2015). This study highlighted the benefit of channelling these emotions to enhance the ability to cope with risk on a personal level and ultimately lead to safer care.

Worry, concern and fear appeared to fuel participant responses to incidences of risk and safety. Affective states can have arousing or motivational properties in decision making (Lerner et al, 2015). Emotions can enhance attention, cause conflict, compromise cognitive processing and lead to the overriding of rational processes and decision-making bias (Keltner and Lerner, 2010; Garfinkel et al, 2016). Indeed, participants in this study reported feeling the entire continuum of emotions, from feeling like a maverick risk-taker, to paralysing fear and dread.

Participants also professed to feeling professionally vulnerable. Worry or concern for some participants lead to avoidance. This can be related to cognitive avoidance theory (Ruscio and Borkovec, 2004) and intolerance of uncertainty (Koerner and Dugas, 2006). Indeed, the ‘knowledge’ theme identified that practitioners lack of knowledge in specific aspects may increase the risk to patients. Understanding the role of this knowledge deficit provides an opportunity for practitioners to push themselves to develop a deep understanding of the profession.

According to the findings of this study, dealing with risk and patient safety can be harrowing. Indeed, for the participants, excessive worry or fear could lead to sleepless nights, avoidance, defensive practice and rules being followed blindly, rather than being applied according to individual patients' situations. A greater understanding and support for ANPs in managing and coping with these feelings of concern and worry is crucial to enable risk to be managed effectively and safely. Sharing risk with others was a source of comfort for the participants in this study.

Implications for practice

These findings have implications for the preparation, training, teaching, education and development, recruitment and retention of ANPs globally. The provision of ongoing educational and emotional support within practice is vital, regarding facilitating the learning and development of practitioners, and helping inform their experiences of managing clinical risk safely in a way that reflects the reality of practice. Potential measures that could aid practitioners in developing constructive risk management and risk-adverse skills include:

Future studies in this field should broaden their scope to improve the data quality and rigour of results. Potential measures could include:

Limitations

This study was limited by the author's competence regarding interviewing, data analysis and application of rigour and trustworthiness. A homogeneous sample of 10 ANPs from similar settings in close geographical proximity has a potential of bias. While the participant sex ratio was equal (five men and five women), the impact of varied experience and expertise was not fully explored. The data may also have been limited by the assumption that the interviews were conducted honestly and accurately (Fontana and Frey, 2008). Indeed, reliance on self-reporting lacks generalisability, rigour and is prone to bias (Jensen and Rodgers, 2002). Exploration of outcomes for comparative insight of perceived effectiveness of risk management to strengthen data was not conducted in this study. Participants' member checking of themes could have enhanced trustworthiness (Birt et al, 2016).

Conclusions

Heideggerian phenomenology provided a unique lens through which to explore insights into the lived world of ANP risk and safety management. These ANPs managed risk from a perspective of care or concern towards their patients and situations. Coping with risk varied according to moods, which both guided and hindered practice. Channelling emotions such as concern, worry and fear may enhance capacity and capability to cope with risk, and ultimately lead to safer care. Participants' efforts to keep patients safe from harm influenced how they managed risk and safety. Experiences of risk also represent an opportunity to learn, develop and potentially advance practice.